After leaving the increasingly nonsensical 10cc, Kevin Godley and Lol Creme worked together on a number of albums which demonstrated their interest in elliptical songwriting and esoteric lyrical themes, wordplay, technical skill, studiocraft and silliness. Having the audacity (and idiocy) to launch their new career in the midst of the punk era with an absurdly complex triple album the world was pretty much set against Godley & Creme from the start. Listening to the compilation album Images (1994), which covers their post-10cc career through to 1988, serves as a reminder of just how redundant pretty much everything they did actually was. In a way that's a shame, because they were extremely smart, very interested in music and it's technological framing, but they just happened to be making their ridiculous records at precisely the wrong time. By the mid-1980's they had realised that just being smart-alecks mucking around wasn't really working and released a few much more straightforward songs that struck a clearer chord with the record buying public and in fact mega-smash 'Cry' and 'Under Your Thumb' are really very decent pop songs. The trouble is that it's all in the context of absolute garbage like 'My Body the Car' and 'Lost Weekend'. In 10cc, when Godley and Creme were getting too elaborate they always had Graham Gouldman's pop smarts to keep at least one of their feet on the ground, but without him most of their stuff is just all over the show and often maddeningly irritating. Mind you, if they hadn't been trying so much stuff out we wouldn't have had the utter brilliance of 'I Pity Inanimate Objects' which, with it's wildly pitch-shifting vocals, is (unintentionally) one of the funniest things I've ever heard in my life.

We all love Godspeed You! Black Emperor of course, but did we ever really actually listen properly to the records I wonder. Because in retrospect they're surprisingly hollow. Much like the band's laughably confused and moronically overblown ideological bluster, the records don't really amount to much more than an impressive but meaningless noise which reveals its lack of depth quite shockingly only once it's over. I remember seeing them at the Sussex Arts Club in Brighton when their first album F#A#∞ (1997) was released and being struck by how ironic it was that all of the audience who would loathe Mike Oldfield were basically listening to what at the time amounted to little more than an Oldfield covers band. Anyway, the album was hugely important mainly because it diluted a lot of avant-classical that was being written and recorded by all sorts of interesting people at the time and added a drum kit and electric guitar, thereby making it officially palatable by the indie kids, and to really hook them in the record came with a selection of enigmatic documents and artefacts (the penny crushed under a train wheel was the real clincher) adding a true air of mystery to the whole thing which was incredibly appealing. To open the album with the spoken words "we are trapped in the belly of this horrible machine, and the machine is bleeding to death" should, of course, have been a tongue-in-cheek introduction to heartfelt political rhetoric, but a more humourless band than Godspeed You! Black Emperor I challenge you to find and therefore I fear it really represents the band's own inability to apply logic to their own arguments (which is a great shame because politically I'm in total agreement with their point of view. Except to say that for a band so overtly critical of a corporate world they seem to have a pretty aggressive handle on marketing techniques...). Where the attitude and the approach could have led to something devastating, instead what they delivered is what people insisted and insisted on referring to as "apocalyptic", with rising waves of strings, guitar and drums building to florid but sinister crescendos. It's still got some power, but the simple truth really is that it's Cave-In played by a string section with a little bit of Oldfield for good measure. To be completely honest I still really like it and really rate it, but I simply can't take it seriously and the idea that we all went so crazy about it seems, in retrospect, utterly absurd.

The 1999 mini-LP that followed, Slow Riot for New Zero Kanada, was better, more focussed and, much more than the fuzzy and painfully strained F#A#∞, managed to create the sense of internal tension which is absolutely necessary for this type of build up, break down music to succeed. The two pieces on Slow Riot are more convincing probably because they're more honest in their bombastic nature and as such make a decent argument for a lack of real dramatic subtlety. Where Rachel's gracefully manage to create a sense of the sublime from similar material, Godspeed have always only managed to do the equivalent of stand on a street corner ranting about anarchism, but it's not really a problem when the ranting is this committed.

Far and away the finest record they've made to date is 2000's Lift Your Skinny Fists Like Antennas to Heaven. It's four 20-minute pieces of symphonic art-rock of the most blusteringly pompous kind and in some ways it led to a bizarre reappraisal of prog rock in the music press because they realised that it would be hypocrisy of the most egregious kind to rave about this album and maintain their loathing of prog. Because this is a prog rock record with absolutely no doubt, indeed it's more prog than most prog records. The only difference is that Godspeed's determination to create complex musical structures comes from lofty ambition rather than showing off technical skill. These ebbing and flowing rolling waves of pieces are really impressive, not least because there's an absolute commitment to atmosphere and the whole thing works much better than the previous albums because, for the most part, the band have accepted that they simply don't have the musical imagination or skill to properly utilise the strings as the driver to the music and therefore are much more traditional in their foundation on the materials of rock music. It's all dense and atmospheric stuff, and although there's still an overwhelming sense of being shouted at about the state of the world by a pretentious eleven year old, it's a pretty big achievement.

And so to something so lacking in pretension it represents the diametric opposite of everything Godspeed stand for. I gave away my copy of the first Go-Go's album, Beauty and the Beat, when I thought I had inherited a CD of it, but when I got round to listening to it I discovered that I'd actually only inherited the CD case. So it's straight on to the second, sadly much weaker, album, Vacation (1982). The album gets off to something of a misleading start with the fantastic title song, which is about as bouncy and flippant as pop gets, and that's, of course, a compliment. Thereafter the album is a patchy affair, and unlike the debut album, it's sadly lacking in a sense of excitement or fun (Beauty and the Beat sounds exactly like an impromptu get together of some super-fun-loving young women and is brilliant as a result (as well as having such blistering stuff as 'Our Lips Are Sealed' on it)). Although Vacation is still really bright and cheerful it doesn't have the devil-may-care feel and it sounds too much as if it was a studio bound affair. Jane Wiedlin is still in fine form as a songwriter and there's great stuff here ('Girl of 100 Lists', 'This Old Feeling') and there's a focus on the band as a functioning unit which does show that they had the chops, but ironically it's the ramshackle nature of the first album that feels so sadly lacking. Nevertheless even counting Vacation as less than a total success it still shows that the Go-Go's were one of the truly great pop bands.

Tuesday 12 February 2013

Monday 11 February 2013

LaRM day 179 (Go-Betweens - God is My Co-Pilot)

The week starts off this time around with more from the Go-Betweens, kicking off with their last (pre-reformation) album, 16 Lovers Lane (1988). In some ways 16 Lovers Lane was the perfection of the band's art. It takes all the finest elements of Tallulah, strips out a lot of the over-production (only the processed drums really date the album this time) and leaves some absolutely luminous indie-rock. These are rock songs as pop, absolutely pristine in their arrangement and McLennan's purely instintive sense of melody and romance are what clearly define the record, even taking Forster's jagged style and jagged cynicism and transforming them into gloriously lush pop songs. It's a really wonderful album and the opening trio of 'Love Goes On', 'Quiet Heart' and 'Love is a Sign' are clear signifiers that there wasn't ever going to be a successful commercial career if this album didn't become a smash. It didn't and the Go-Betweens called it quits, leaving behind a body of work of uncommon grace, intellect and charm and it still seems astonishing that to this day they remain something of a cult band. Where Tallulah suffered from over-reaching, 16 Lovers Lane is just pure grace, the string arrangements are much subtler, the chiming guitars setting tone rather than dominating and the easy, fluid melodies are completely natural. The other remarkable thing about 16 Lovers Lane is that, for a band deeply entrenched in notions of romaticism and nostalgia, it's far and away their most romantic album, packed full of heartbreak, yearning and loss, all presented as swooning beauty. It's also worth noting that the closest that the band ever came to proper chart success was the single 'Streets of Your Town' which is one of McLennan's slyest pop songs - musically it's pure, glorious, pop fodder, but (typically for McLennan) it takes a while to realise that you're joyfully singing along to a lyrically heartbreaking song about domestic abuse.

At the end of the band's career a compilation was released, simply entitled 1978-1990. It covered everything from their first 7"'s (the brilliant, scrappy, 'Lee Remick', 'People Say' and 'I Need Two Heads') to the single release of 'Love Goes On' in 1989. It's a good overview, with one album taking on the biggest tracks from the studio LPs and a second album covering the singles, B-sides and rarities, and that's where the most interesting stuff is. Of course, there's McLennan's legendary 'Cattle and Cane', which people often suggest is the most evocatively "Australian" pop song ever written (although the band's early debt to the Cure is pretty evident), and the lovely 'You Won't Find It Again', but there are also wonderful songs in one of Forster's final Go-Betweens numbers 'Rock and Roll Friend' and the melancholic 'This Girl, Black Girl'.

In 1999 tapes of recordings that McLennan and Forster had made in 1978 with the intention of putting out an album surfaced and were released, in all their cruddily recorded glory, as 78 'til 79: The Lost Album. Most of the material was recorded live to a two-track tape recorder (in other words, in exactly the same way that we all did when we were young...) and it's a mixed bag. Unsurprisingly it's the stuff that's slightly better recorded that stands out ('The Sound of Rain', 'Lee Remick', and 'People Say' in particular) but it's evident throughout (even when the sound drops out because the tape was so knackered) that McLennan and Forster were already pretty adept at turning a pop melody and although this is all self-consciously artsy and deliberately underwritten, the seeds of great songwriting are discernible here.

In 2000 Forster and McLennan got back together and, with the help of US indie act Quasi, recorded a new album, 12 years after the release of 16 Lovers Lane. The Friends of Rachel Worth (2000) is a delicate pop-rock album, which has all of the grace and style of the later previous albums, but also has a patience and maturity befitting their advanced ages. There's no urgency and there's no grit to The Friends of Rachel Worth, but to be honest that's entirely appropriate and entireyl fitting and just makes for a comforting listen. McLennan's opener 'Magic In Here' is another of his glittering pop melodies and it's a lovely, unhurried and unfussy reintroduction to a band who's reputation never diminished over the intervening years. There are lots of great, gentle songs here, with the wistful, nostalgic touches that were always evident in their work brought to the fore. 'Surfing Magazines' is a lovely, rolling pop song, 'The Clock' harks back to Forster's ragged style, but with a comforting smoothness, and 'Going Blind' is the kind of song that any number of Beachwood Sparks style US bands dream about being able to write. There's a suprisingly heavy reliance on acoustic guitars which always played a more supporting role previously, but it goes with the casual maturity on show generally and although some felt that there wasn't enough of the band's clever cynicism on display, it's actually just proof that Forster and McLennan were able to grow old gracefully. The pair released two more albums as the Go-Betweens, in 2003 and 2005 respectively, but very sadly McLennan passed away in 2006 at the age of 48, leaving behind some wonderful songs and a reputation as both a foremost songwriter and an all-round decent bloke.

On so on to something very different, it's Italian prog-rock soundtrack pioneers Goblin. Now, I love Dario Argento's film Suspiria with a real passion, but it wouldn't be the work of maverick genius that it is without the exceptional score by Goblin (indeed all of Argento's films with Goblin soundtracks are elevated by them), and neither would his earlier film, Profondo Rosso (1975) be as good as it is without Goblin's contribution. The awe-inspiring Italian reissue label Dagored put out a number of Goblin's soundtracks with astonishing new packaging, the second of which was the Profondo Rosso soundtrack, and it's fantastic. It rips off pretty much everything going (the track 'Mad Puppet' is built around a riff and sound stolen directly from Mike Oldfield's Tubular Bells) and its shameless prog-rock thefts only go to enhance their already surprising deftness with an overblown sound. The title track is brilliantly propulsive and works as a piece of grinding prog as well as it does a scene setting piece of instrumental score, 'Wild Session' is a sinisterly groovy bass, buzzing keyboard and sax freak-out, and 'Deep Shadows' shows an equally heavy debt to Emerson, Lake & Palmer and 60's garage rock. It's a fantastic and fantastically over-the-top record, which actually holds up amazingly well, both as a nervy soundtrack to a tense piece of giallo filmmaking and as an exercise in European prog.

Certainly Goblin's greatest achievement came two years later, soundtracking Argento's finest movie, Suspiria. The film itself is a kaleidoscopic trip into Argento's fevered imagination and Goblin's supremely spooky soundtrack was the perfect complement. The opening title track, whose first half, with it's anxious, strummed mandolins, booming, ritualistic drum and squealing keyboard is a masterclass in creating tension, and when it breaks open into a pounding, claustrophic rock piece halfway through it ups the tension even further. Taken out of context it can possibly sound a little silly (alright, very silly), but it's nonetheless a superb example of the art of soundtrack writing. 'Witch' has rattling, clacking percussion, electronic noises, deep, throbbing hums and mysterious shrieks and wails and is another great example of how to sound completely spooked-out. It's all really quite pioneering stuff, considering that horror soundtracks had previously relied almost exclusively on orchestras to create the requisite unease, and using a rock band was an unusual choice, and one which you wouldn't have imagined could have done such a supreme job of sounding so terrifying. 'The Sighs' is another great example, it sounds exactly like a nightmare. The second side isn't quite as compelling, with the sleazy sax breaks on 'Black Forest' sounding pretty dated, and 'Blind Concert''s squelchy bass is a bit daft, but nevertheless the Suspiria soundtrack is still one of the great examples of just how rock music and film can, occasionally, work seamlessly together, while each can still stand alone.

Presumably having seen Suspiria, George A. Romero approached Goblin to score his Dawn of the Dead (the soundtrack being released in Italy as Zombi in 1978). In keeping with Romero's more tongue-in-cheek approach, the soundtrack is more varied than that for Suspiria, including some silly things such as a bar-room knockabout in 'Torte in Faccia' and a pulsing bit of corny rock in 'Zaratozom', but even so, it's still all really pretty good. Openers 'L'alba dei Morti Viventi' and 'Zombi' are nearly worthy of the Suspiria soundtrack and there are plenty of fine moments, but Goblin really do match the brief - where Suspiria is about unknown supernatural malevolence, Dawn of the Dead is based on good old lumbering zombies, so it's a different kind of creepy that Goblin needed to come up with and they really succeeded. The other big difference is that most of the pieces on Zombi are fairly brief, designed as simple mood setters as opposed to the 7 minute build-ups of the Suspiria work, and as such it's much clearer that this music was designed to suplement rather than exist in its own right, but be that as it may, it's still fine stuff, and all a clear influence on horror soundtrack writers and film directors to come, especially John Carpenter.

Three of the core members of Goblin reunited to record the soundtrack for Argento's 1982 movie, Tenebre. It's another good bit of paranoid, spooked out rock, but this time the brief is more about claustrophobic atmosphere (the story is about a serial killer and has no supernatural elements) and once again, Goblin live up to the brief pretty admirably. The slight difficulty is that this is about context more than ever and of these four soundtracks it's certainly the one that stands alone the weakest. It also suffers a little bit from technological updates (and as we all know, nothing turned out to be more dating to a record than the hot new technology of the late 1970's/early 1980's), and focuses a bit too much on rock posturing. There's great stuff here, don't get me wrong ('Flashing' is a decent scene-setter with some good Kraftwerkian keyboard action), but it rarely reaches the real peaks of their earlier work.

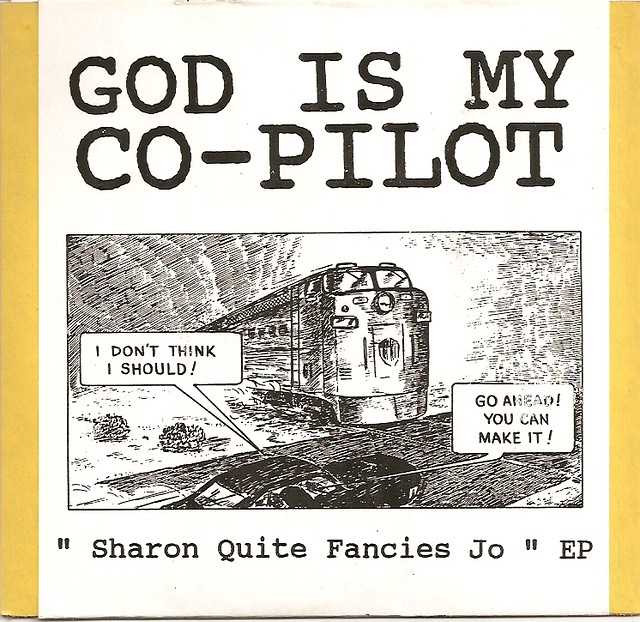

Right, we'll have to race through the hundreds of God Is My Co-Pilot records I've got because hardly any of them have any internet presence and almost all of my copies are on vinyl. As pioneers (and virtual sole practitioners) of a kind of spazz/squonk/queercore/noise outfit, God Is My Co-Pilot were a fascinating creation, representing a kind of US underground which was much truer to the spirit of real experimentalism than pretty much anyone else. As an unpredictable amalgam of punk, jazz, freeform noise and musique concrete, they created a massive body of work in the course of just seven years (partly because this stuff was probably pretty easy to do, but that's not the point). It's either totally pointless, maddening or truly inspirational depending on your taste and personally I think it's all fantastic stuff. Still challenging, still confrontational, still energising, and always surprising, it's the sound of real lives expressing themselves as honestly as possible in their messy, clumsy actuality. It's also really good fun and although I suspect the band themselves were probably utterly po-faced and joyless, it's actually strangely funny a lot of the time. The fact that it's all about gender politics and musical presumption is important, because this is underneath it all, heartfelt stuff and it's worth bearing in mind that although it sounds like noise, it's still intended to be heard. Anyway, that about covers the whole of the following, which I can't find more than a handful of 30 - 60 second songs from: I Am Not This Body LP, How I Got Over 7", Gender Is As Gender Does 7" (all 1992), My Sinister Secret Agenda 7", Probable Cause split-7", Getting Out of Boring Time Getting Into Boring Pie mini-LP (all 1993), Sharon Quite Fancies Jo 7", More Pretty Girls Than One 7", How To Be LP and Rough Trade Singles Club 7" (all 1994).

I can't even find cover images for How To Be and the Rough Trade Singles Club 7". Anyway, the only God Is My Co-Pilot record that I can really talk about now is the 1993 album Speed Yr Trip, which I have on CD. Speed Yr Trip is more of the same, unpredictable, shouty, short, sharp and brutal missives from the gender gap. Bearing in mind that only three of the album's 26 songs is over the 2 minute mark you'll see what I mean when I say that these are vicious little bites, but whose aim is to create an atmosphere of engagement. There are moments when it all seems surprisingly lucid (the tightly structured 'Woman Enough' for instance) but these are few and far between. In any event, it's all exciting stuff, and bears comparison with Japan's foremost exponents of spazz rock, Melt Banana, whose brain-bendingly erratic output is more visceral, but less intellectually engaged than God Is My Co-Pilot's.

At the end of the band's career a compilation was released, simply entitled 1978-1990. It covered everything from their first 7"'s (the brilliant, scrappy, 'Lee Remick', 'People Say' and 'I Need Two Heads') to the single release of 'Love Goes On' in 1989. It's a good overview, with one album taking on the biggest tracks from the studio LPs and a second album covering the singles, B-sides and rarities, and that's where the most interesting stuff is. Of course, there's McLennan's legendary 'Cattle and Cane', which people often suggest is the most evocatively "Australian" pop song ever written (although the band's early debt to the Cure is pretty evident), and the lovely 'You Won't Find It Again', but there are also wonderful songs in one of Forster's final Go-Betweens numbers 'Rock and Roll Friend' and the melancholic 'This Girl, Black Girl'.

In 1999 tapes of recordings that McLennan and Forster had made in 1978 with the intention of putting out an album surfaced and were released, in all their cruddily recorded glory, as 78 'til 79: The Lost Album. Most of the material was recorded live to a two-track tape recorder (in other words, in exactly the same way that we all did when we were young...) and it's a mixed bag. Unsurprisingly it's the stuff that's slightly better recorded that stands out ('The Sound of Rain', 'Lee Remick', and 'People Say' in particular) but it's evident throughout (even when the sound drops out because the tape was so knackered) that McLennan and Forster were already pretty adept at turning a pop melody and although this is all self-consciously artsy and deliberately underwritten, the seeds of great songwriting are discernible here.

In 2000 Forster and McLennan got back together and, with the help of US indie act Quasi, recorded a new album, 12 years after the release of 16 Lovers Lane. The Friends of Rachel Worth (2000) is a delicate pop-rock album, which has all of the grace and style of the later previous albums, but also has a patience and maturity befitting their advanced ages. There's no urgency and there's no grit to The Friends of Rachel Worth, but to be honest that's entirely appropriate and entireyl fitting and just makes for a comforting listen. McLennan's opener 'Magic In Here' is another of his glittering pop melodies and it's a lovely, unhurried and unfussy reintroduction to a band who's reputation never diminished over the intervening years. There are lots of great, gentle songs here, with the wistful, nostalgic touches that were always evident in their work brought to the fore. 'Surfing Magazines' is a lovely, rolling pop song, 'The Clock' harks back to Forster's ragged style, but with a comforting smoothness, and 'Going Blind' is the kind of song that any number of Beachwood Sparks style US bands dream about being able to write. There's a suprisingly heavy reliance on acoustic guitars which always played a more supporting role previously, but it goes with the casual maturity on show generally and although some felt that there wasn't enough of the band's clever cynicism on display, it's actually just proof that Forster and McLennan were able to grow old gracefully. The pair released two more albums as the Go-Betweens, in 2003 and 2005 respectively, but very sadly McLennan passed away in 2006 at the age of 48, leaving behind some wonderful songs and a reputation as both a foremost songwriter and an all-round decent bloke.

On so on to something very different, it's Italian prog-rock soundtrack pioneers Goblin. Now, I love Dario Argento's film Suspiria with a real passion, but it wouldn't be the work of maverick genius that it is without the exceptional score by Goblin (indeed all of Argento's films with Goblin soundtracks are elevated by them), and neither would his earlier film, Profondo Rosso (1975) be as good as it is without Goblin's contribution. The awe-inspiring Italian reissue label Dagored put out a number of Goblin's soundtracks with astonishing new packaging, the second of which was the Profondo Rosso soundtrack, and it's fantastic. It rips off pretty much everything going (the track 'Mad Puppet' is built around a riff and sound stolen directly from Mike Oldfield's Tubular Bells) and its shameless prog-rock thefts only go to enhance their already surprising deftness with an overblown sound. The title track is brilliantly propulsive and works as a piece of grinding prog as well as it does a scene setting piece of instrumental score, 'Wild Session' is a sinisterly groovy bass, buzzing keyboard and sax freak-out, and 'Deep Shadows' shows an equally heavy debt to Emerson, Lake & Palmer and 60's garage rock. It's a fantastic and fantastically over-the-top record, which actually holds up amazingly well, both as a nervy soundtrack to a tense piece of giallo filmmaking and as an exercise in European prog.

Certainly Goblin's greatest achievement came two years later, soundtracking Argento's finest movie, Suspiria. The film itself is a kaleidoscopic trip into Argento's fevered imagination and Goblin's supremely spooky soundtrack was the perfect complement. The opening title track, whose first half, with it's anxious, strummed mandolins, booming, ritualistic drum and squealing keyboard is a masterclass in creating tension, and when it breaks open into a pounding, claustrophic rock piece halfway through it ups the tension even further. Taken out of context it can possibly sound a little silly (alright, very silly), but it's nonetheless a superb example of the art of soundtrack writing. 'Witch' has rattling, clacking percussion, electronic noises, deep, throbbing hums and mysterious shrieks and wails and is another great example of how to sound completely spooked-out. It's all really quite pioneering stuff, considering that horror soundtracks had previously relied almost exclusively on orchestras to create the requisite unease, and using a rock band was an unusual choice, and one which you wouldn't have imagined could have done such a supreme job of sounding so terrifying. 'The Sighs' is another great example, it sounds exactly like a nightmare. The second side isn't quite as compelling, with the sleazy sax breaks on 'Black Forest' sounding pretty dated, and 'Blind Concert''s squelchy bass is a bit daft, but nevertheless the Suspiria soundtrack is still one of the great examples of just how rock music and film can, occasionally, work seamlessly together, while each can still stand alone.

Presumably having seen Suspiria, George A. Romero approached Goblin to score his Dawn of the Dead (the soundtrack being released in Italy as Zombi in 1978). In keeping with Romero's more tongue-in-cheek approach, the soundtrack is more varied than that for Suspiria, including some silly things such as a bar-room knockabout in 'Torte in Faccia' and a pulsing bit of corny rock in 'Zaratozom', but even so, it's still all really pretty good. Openers 'L'alba dei Morti Viventi' and 'Zombi' are nearly worthy of the Suspiria soundtrack and there are plenty of fine moments, but Goblin really do match the brief - where Suspiria is about unknown supernatural malevolence, Dawn of the Dead is based on good old lumbering zombies, so it's a different kind of creepy that Goblin needed to come up with and they really succeeded. The other big difference is that most of the pieces on Zombi are fairly brief, designed as simple mood setters as opposed to the 7 minute build-ups of the Suspiria work, and as such it's much clearer that this music was designed to suplement rather than exist in its own right, but be that as it may, it's still fine stuff, and all a clear influence on horror soundtrack writers and film directors to come, especially John Carpenter.

Three of the core members of Goblin reunited to record the soundtrack for Argento's 1982 movie, Tenebre. It's another good bit of paranoid, spooked out rock, but this time the brief is more about claustrophobic atmosphere (the story is about a serial killer and has no supernatural elements) and once again, Goblin live up to the brief pretty admirably. The slight difficulty is that this is about context more than ever and of these four soundtracks it's certainly the one that stands alone the weakest. It also suffers a little bit from technological updates (and as we all know, nothing turned out to be more dating to a record than the hot new technology of the late 1970's/early 1980's), and focuses a bit too much on rock posturing. There's great stuff here, don't get me wrong ('Flashing' is a decent scene-setter with some good Kraftwerkian keyboard action), but it rarely reaches the real peaks of their earlier work.

Right, we'll have to race through the hundreds of God Is My Co-Pilot records I've got because hardly any of them have any internet presence and almost all of my copies are on vinyl. As pioneers (and virtual sole practitioners) of a kind of spazz/squonk/queercore/noise outfit, God Is My Co-Pilot were a fascinating creation, representing a kind of US underground which was much truer to the spirit of real experimentalism than pretty much anyone else. As an unpredictable amalgam of punk, jazz, freeform noise and musique concrete, they created a massive body of work in the course of just seven years (partly because this stuff was probably pretty easy to do, but that's not the point). It's either totally pointless, maddening or truly inspirational depending on your taste and personally I think it's all fantastic stuff. Still challenging, still confrontational, still energising, and always surprising, it's the sound of real lives expressing themselves as honestly as possible in their messy, clumsy actuality. It's also really good fun and although I suspect the band themselves were probably utterly po-faced and joyless, it's actually strangely funny a lot of the time. The fact that it's all about gender politics and musical presumption is important, because this is underneath it all, heartfelt stuff and it's worth bearing in mind that although it sounds like noise, it's still intended to be heard. Anyway, that about covers the whole of the following, which I can't find more than a handful of 30 - 60 second songs from: I Am Not This Body LP, How I Got Over 7", Gender Is As Gender Does 7" (all 1992), My Sinister Secret Agenda 7", Probable Cause split-7", Getting Out of Boring Time Getting Into Boring Pie mini-LP (all 1993), Sharon Quite Fancies Jo 7", More Pretty Girls Than One 7", How To Be LP and Rough Trade Singles Club 7" (all 1994).

I can't even find cover images for How To Be and the Rough Trade Singles Club 7". Anyway, the only God Is My Co-Pilot record that I can really talk about now is the 1993 album Speed Yr Trip, which I have on CD. Speed Yr Trip is more of the same, unpredictable, shouty, short, sharp and brutal missives from the gender gap. Bearing in mind that only three of the album's 26 songs is over the 2 minute mark you'll see what I mean when I say that these are vicious little bites, but whose aim is to create an atmosphere of engagement. There are moments when it all seems surprisingly lucid (the tightly structured 'Woman Enough' for instance) but these are few and far between. In any event, it's all exciting stuff, and bears comparison with Japan's foremost exponents of spazz rock, Melt Banana, whose brain-bendingly erratic output is more visceral, but less intellectually engaged than God Is My Co-Pilot's.

Friday 8 February 2013

LaRM day 178 (Global Communication - Go-Betweens)

Probably the single greatest work in the ambient techno field, Global Communication's 1994 album 76:14 is a work of absolutely stunning beauty. While Richard James was fiddling with Eno's flat-lining end of ambience to create a sense of cynical menace, Mark Pritchard and Tom Middleton chose instead to refine the melodic part of Eno's work into an incredibly graceful piece of glacial, drifting melody. The album taken as a whole can be seen as a series of interconnected movements, tied together by haunting, delicate melodies which glide throughout the work in a continuous flow, and whether it's Eno's extraterrestrial ambience or the lighter end of Kraftwerk's motorik that forms the frame, it's the ethereal melodies which really drive the album. In some ways it fails as a true work of ambient house or ambient techno because it really can't take a backseat as, despite the fact that it's a slow-burning wash of noise, it's absolutely arresting, you simply can't use it as background music. One of 76:14's greatest achievements though is its absolute and pure beauty. I think it's highly unusual for a record composed entirely of synthetic noise, conducted through endless processing and created almost wholly of clinical samples to sound so utterly gorgeous, and where usually ambient techno falls foul of its placing in a technological timeline (listen to how terribly dated the Future Sound of London records sound now and you'll see what I mean), 76:14 could have been made yesterday and it would seem as fresh and unchallengably beautiful as it did in 1994. As far as purely electronic music goes I don't think it has ever been bettered.

Many people think highly of the collaboration between Guided By Voices' Robert Pollard and Superchunk's Mac McCaughan but personally I've always thought it to be disappointingly less than the sum of its parts. Bearing in mind that both men trade in pretty heavy duty melody it's all a bit messy and unfocussed and feels very much like they worked on their parts in different rooms. There are some fun pop songs on Calling Zero (2002) (the duo called themselves Go Back Snowball btw) (opener 'Radical Girl' is clear and fun with some cheerful synthesised horns) but on the whole it's too muddy and unwieldy and seems to play on the weaknesses of both rather than the strengths. There are occasional flashes of McCaughan's Portastatic work on 'Go Gold' and 'It Is Divine' but Pollard then introduces his own idiosyncratic take on British invasion melody and makes them less impressive. In fact it's really that each seems to undo the others good work and although it's a perfectly decent album it leaves me a bit cold and acts as a reminder that just because people are really great at what they do it doesn't mean that putting them together will necessarily work.

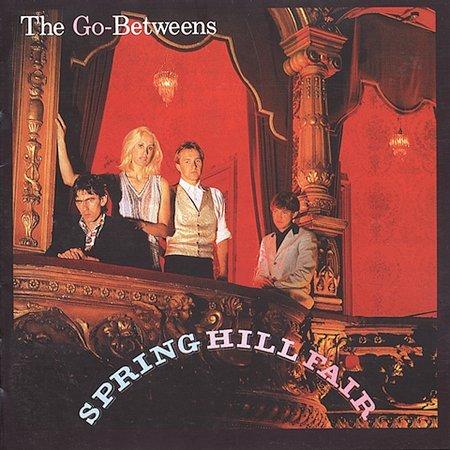

It's quite possible that the Go-Betweens were the best band Australia ever produced. A ramshackle, unpredictable mix of esoteric literary posturing and highly tuned pop nous made for a band who were never less than exciting and always throroughly engaging. The first two albums were spiky, odd, angular and minimal records, cheaply recorded and composed mainly of spindly guitar, bass and Robert Forster and Grant McLennan's artless vocals (with drummer Lindy Morrison adding her four/four drumming to the second). The difference in approach between the two was made explicitly clear from the start with Forster's arch, wordy and strict style contrasting with McLennan's much more pop melody friendly approach. By the third album, 1984's Spring Hill Fair, the trio had been joined by bass player Robert Vickers, allowing McLennan to add second guitar to Forster's lead, and the band's sound was cemented. A much smoother and confident style pervades Spring Hill Fair than the nervy, cold sound of the preceding records, and while Forster's raised eyebrow style still feels slightly aloof and knowing, it's much more accessible than before and his songwriting has matured into something allowing itself to be approachable. 'Part Company' and 'Draining the Pool for You' showed just how far he'd come by combining his jittery songwriting with great, smart storytelling and although his songs were never as straightforwardly enjoyable as McLennan's they were where the real depth of the Go-Betweens was. McLennan's contributions meanwhile are as charming as ever, with 'Bachelor Kisses' being one of his greatest small-town romances.

The seemingly Forster-led Go-Betweens shifts dynamic by fourth album, 1986's Liberty Belle and the Black Diamond Express, with McLennan's much more listener-friendly approach being felt dominantly throughout. It's a fine development for the band, knocking those spiky edges off and leaving a pristinely odd pop band, making utterly charming ramshackle guitar-pop. That's not to say that Forster isn't able to continue his arch mannerisms, but when you listen to 'Bow Down' although you're still getting his smart-arse attitude, you're getting it through a beautifully wistful, accommodating song. There's scarcely a dud moment on Liberty Belle, with McLennan's pop songs blending almost seamlessly with Forster's cleverness, and the relationship between Forster's lyrics (which make Morrissey's read like those of a bone-headed fifteen year-old) and McLennan's more instinctively delicate tales of love and simple life is one of mutual dependence which is oddly inspiring. Opener 'Spring Rain' is one of the Go-Betweens most straightforwardly forthright pop songs and it really sets the tone for an album of great warmth, charm and embracing, inviting intellect.

The following year the band were joined by oboeist, percussionist and vocalist Amanda Brown and the sound and dynamic changed again. There had been plans to make the band successful and part of this operation involved using new producers and recording studios and the resultant album, Tallulah, while still being full of really great songs, sounds off. It's overproduced, it has drum machine patterns, shiny surfaces and the sound doesn't really match the mood and tone of the Go-Betweens' songs. It's a shame because it makes the introduction of Brown's unusual instrumentation sound like it's part of the problem when in reality she brings an interesting light touch to the songs. And as I say, the songs themselves are as pristine as ever. We've got McLennan's fabulous (if lyrically rather brutal) pop song 'Right Here', a summer breeze of a song if ever there was one, and the wonderful, wistful kiss-off of 'Bye Bye Pride' as well as Forster's stabbing, jazzy and snarky 'Someone Else's Wife' and driving, soaring 'I Just Get Caught Out'. All told it's a really superb album, and it's a shame that (I suspect a record company rather than the band's) ambition meant that it was recorded in a way that so clearly dates it. The copy I've got has a second disc of B-sides and rarities, which are a mixed bag, but there are some nice second tier tunes in 'A Little Romance' and 'Don't Call Me Gone' and decent alternative versions of 'Right Here' and 'I Just Get Caught Out'.

Many people think highly of the collaboration between Guided By Voices' Robert Pollard and Superchunk's Mac McCaughan but personally I've always thought it to be disappointingly less than the sum of its parts. Bearing in mind that both men trade in pretty heavy duty melody it's all a bit messy and unfocussed and feels very much like they worked on their parts in different rooms. There are some fun pop songs on Calling Zero (2002) (the duo called themselves Go Back Snowball btw) (opener 'Radical Girl' is clear and fun with some cheerful synthesised horns) but on the whole it's too muddy and unwieldy and seems to play on the weaknesses of both rather than the strengths. There are occasional flashes of McCaughan's Portastatic work on 'Go Gold' and 'It Is Divine' but Pollard then introduces his own idiosyncratic take on British invasion melody and makes them less impressive. In fact it's really that each seems to undo the others good work and although it's a perfectly decent album it leaves me a bit cold and acts as a reminder that just because people are really great at what they do it doesn't mean that putting them together will necessarily work.

It's quite possible that the Go-Betweens were the best band Australia ever produced. A ramshackle, unpredictable mix of esoteric literary posturing and highly tuned pop nous made for a band who were never less than exciting and always throroughly engaging. The first two albums were spiky, odd, angular and minimal records, cheaply recorded and composed mainly of spindly guitar, bass and Robert Forster and Grant McLennan's artless vocals (with drummer Lindy Morrison adding her four/four drumming to the second). The difference in approach between the two was made explicitly clear from the start with Forster's arch, wordy and strict style contrasting with McLennan's much more pop melody friendly approach. By the third album, 1984's Spring Hill Fair, the trio had been joined by bass player Robert Vickers, allowing McLennan to add second guitar to Forster's lead, and the band's sound was cemented. A much smoother and confident style pervades Spring Hill Fair than the nervy, cold sound of the preceding records, and while Forster's raised eyebrow style still feels slightly aloof and knowing, it's much more accessible than before and his songwriting has matured into something allowing itself to be approachable. 'Part Company' and 'Draining the Pool for You' showed just how far he'd come by combining his jittery songwriting with great, smart storytelling and although his songs were never as straightforwardly enjoyable as McLennan's they were where the real depth of the Go-Betweens was. McLennan's contributions meanwhile are as charming as ever, with 'Bachelor Kisses' being one of his greatest small-town romances.

The seemingly Forster-led Go-Betweens shifts dynamic by fourth album, 1986's Liberty Belle and the Black Diamond Express, with McLennan's much more listener-friendly approach being felt dominantly throughout. It's a fine development for the band, knocking those spiky edges off and leaving a pristinely odd pop band, making utterly charming ramshackle guitar-pop. That's not to say that Forster isn't able to continue his arch mannerisms, but when you listen to 'Bow Down' although you're still getting his smart-arse attitude, you're getting it through a beautifully wistful, accommodating song. There's scarcely a dud moment on Liberty Belle, with McLennan's pop songs blending almost seamlessly with Forster's cleverness, and the relationship between Forster's lyrics (which make Morrissey's read like those of a bone-headed fifteen year-old) and McLennan's more instinctively delicate tales of love and simple life is one of mutual dependence which is oddly inspiring. Opener 'Spring Rain' is one of the Go-Betweens most straightforwardly forthright pop songs and it really sets the tone for an album of great warmth, charm and embracing, inviting intellect.

The following year the band were joined by oboeist, percussionist and vocalist Amanda Brown and the sound and dynamic changed again. There had been plans to make the band successful and part of this operation involved using new producers and recording studios and the resultant album, Tallulah, while still being full of really great songs, sounds off. It's overproduced, it has drum machine patterns, shiny surfaces and the sound doesn't really match the mood and tone of the Go-Betweens' songs. It's a shame because it makes the introduction of Brown's unusual instrumentation sound like it's part of the problem when in reality she brings an interesting light touch to the songs. And as I say, the songs themselves are as pristine as ever. We've got McLennan's fabulous (if lyrically rather brutal) pop song 'Right Here', a summer breeze of a song if ever there was one, and the wonderful, wistful kiss-off of 'Bye Bye Pride' as well as Forster's stabbing, jazzy and snarky 'Someone Else's Wife' and driving, soaring 'I Just Get Caught Out'. All told it's a really superb album, and it's a shame that (I suspect a record company rather than the band's) ambition meant that it was recorded in a way that so clearly dates it. The copy I've got has a second disc of B-sides and rarities, which are a mixed bag, but there are some nice second tier tunes in 'A Little Romance' and 'Don't Call Me Gone' and decent alternative versions of 'Right Here' and 'I Just Get Caught Out'.

Thursday 7 February 2013

LaRM day 177 (Dana Gilllespie-Glass Candy)

Alright, so it's the late-1960's, you're the daughter of an ennobled eminent Austrian scientist and you're living in the UK, so what do you do with your time? What kind of career do you want? To follow in the family footsteps and make great strides in the advancement of human understanding? Or how about hanging out with stupid hippies, taking your clothes off for low-rent movies and making drippy records? The latter? If you're Dana Gillespie, you've got it. Dana Gillespie (or to give her the name her family knew her by, Richenda Antoinette de Winterstein Gillespie) released her second album, Box of Surprises, in 1969 and it's exactly the kind of watercolour psychedelia you'd expect from a singer with so little engagement, but that's not to say that it isn't great. Like its predecessor Foolish Seasons, and as its cover depicting Gillespie surrounded by various stuffed animals suggests, it's a near perfect snapshot of the good, the bad and everything in between that the British and American pop scenes were concentrating on at the time. There are bouncy Dusty Springfield take-offs ('Describing You', 'You're Heartbreak Man') and there are folkie west coast workouts ('For David, the Next Day', 'Foolish Seasons'), there's low-level psychedelia ('Like I'm a Clown', 'Taffy') and delicate balladry ('When Darkness Fell', 'By Chasing Dreams'). It's all really fantastic stuff, less because it's particularly brilliant in itself but because it's a superb summation of so much of what was going on at the time and it's a whole load of fun.

Speaking of folkie freakery here's the soundtrack to possibly the UK's greatest horror film, The Wicker Man (1973) (the only rival to The Wicker Man for the UK horror crown is the awesome Blood on Satan's Claw which mines similar material). The Wicker Man soundtrack was overseen by New Yorker Paul Giovanni, but is really mostly the work of obscure UK folk outfit Magnet, and is suitably unnerving, off-beat and spooky. I don't think it was ever given an official release as such and was put out by indie labels many years after the film's release, and the vinyl issue that I've got breaks the material into two distinct sides, the first being the fuller songs and the second being the incidental music. It's all proto freak-folk of the highest order throughout and you can hear where pretty much all of the 2000's freak-folk scene got their ideas. While Espers have tried hard to make out that it was Lubos Fiser's work on Valerie and Her Week of Wonders that inspired them, that's clearly nonsense as their records are nothing like Fiser's and are too genetically identical to The Wicker Man for it to be ignored. In any event the songs on the first side have spooky reed instruments winding their wobbly way through the acoustic guitar and vocal pieces, with the over-riding sexual impetus of the lyrics matching the same theme of the film perfectly. It all sounds suitably pagan and disconcerting, it's all entirely appropriate and you can easily imagine this stuff being played while nutty heathen rites are being performed. We've got the frightening children's round of 'Maypole', the blisteringly erotic yearning of 'Willow's Song', the bar-room filth of 'Landlord's Daughter', all of which bring the scenes in the film vividly back to mind. The incidental music on the second side is in some ways more interesting, because it really brings out the essential spookiness of this stuff, most of it being traditional music adapted for the film. There's a really deeply unsettling feel to a lot of it which chimes absolutely with the film's theme of the distance between cultures over time and although it seems silly to think about paganism as something potentially horrifying, The Wicker Man and its soundtrack demonstrate that our innate fears about collective behaviour are exercised through our fear of the past.

Here comes one that I would slate without mercy were it not for my own past. I remember being in Arles in the south of France in the blistering summer of 1988, about a month after the release of the Gipsy Kings' breakthrough single 'Bamboleo'. In the centre of Arles is a spectacular Roman amphitheatre and one night we were in town and heard, clear as day, the Gipsy Kings performing inside. It was truly an amazing evening, incredibly romantic, with the townsfolk all gathered in and around the amphitheatre going mad for the Gipsy Kings, the town beautifully lit up on a sweltering night, scorpions and foxes darting around and this faux-traditional music. It really was great. Obviously the Gipsy Kings debut album (and 7" 'Djobi Djoba' which I also bought) is pretty daft and a little silly sounding now, and the idea that it caught on so wildly with the proto Womad crowd shows, I suppose, that it wasn't any good, but I'm not going to slag it off, so there.

Girls Against Boys were making their finest work at the same time as the Afghan Whigs and although the Whigs were and have always been markedly better, there was a shared sense of urgency, a similarly misanthropic take on relationships and a musical brittleness in common. Listening to House of Girls Against Boys (1996) now it's surprising both how good the songs are and how dated the sound of it is. The whole thing starts with some brilliant, vicious bit of slicing guitar work on 'Super-Fire' and the jolting 'Click Click', and these two set the tone for the juddering, halting structures of the songs. The entire album is a close, claustrophobic rock record which, although never quite getting to the psychic depths that Greg Dulli can reach, is a bleak, black exercise in rock dynamics. Even when it slows down, it does so only in order to become even more dark and laden with foreboding (the grim 'Life in Pink' for instance), and the jagged rock songs are if anything a respite from the grim atmospherics. There's a kind of evil lounge rock on 'TheKindaMzkYouLike', which goes to pains to recreate the Afghan Whigs style, with an added pop backbeat, and 'Cash Machine' is a grinding, less violent kind of Big Black number. It's a really good album and although its production style means that you could probably guess which year it was made in without any difficulty, it's got some superb songs and an impressive attitude.

You know how Vampire Weekend weren't actually any good? If you can imagine what they might sound like if they were in fact really great, then you've imagined Givers. Their song 'Up Up Up' became a minor thing thanks to being included on the soundtrack to some stupid football computer game, (and horrifyingly was also used in an episode of Glee I believe) but forget the computer game (and particularly forget about Glee), focus on the tune, it's a quite brilliant explosion of bright, frantic pop music at its absolute finest, a rainbow of jittery "afro" guitar riffs, percussive drive and jaunty dual vocals. It's a brilliant song and although it's the most immediate on their album In Light (2011), it's still demonstrative of their style throughout. I saw them play at last year's Field Day and they were really great, energetic in the best possible way, really exciting. Where Vampire Weekend seemed to think that there was something quite amazing about being white and playing guitar riffs that sound a little bit like African riffing, Givers use the same techniques but blend them into a much bigger and way, way more impressive tapestry of sounds and styles (and don't feel the need to refer to it in interviews and their own lyrics). Givers are also much more technically interesting, forming songs from the ground up and letting them grow outwards, often ending up in very different places to where they started. 'Meantime' is a great, multi-part pop song with fantastically propulsive percussion and typically charming and enlivening vocal interplay between Tiffany Lamson (whose percussion playing is a joy to watch) and Taylor Guarisco, and 'Saw You First' is a beautifully laid-back ramble through melody, and the album is full of songs of the same calibre. There are some tunes that don't quite work (the restless 'Ripe' is a bit forgettable) but on the whole the album is a great, uplifting first outing.

Finally it's the glam racket of Glass Candy's debut Love Love Love (2003). I think that we're all supposed to love Glass Candy now but the only thing to recommend Love Love Love is the excellent gatefold sleeve. Personally I think it's a terrible record, lazy, boring and self-indulgent without the good grace to be over the top. It's an attempt at being louche in a kind of Bowie by Can kind of way and it's such an inept failure that I'm absolutely mystified as to what it is that we're supposed to be pretending to see in it. Behind the ghastly shrieking vocals (which, according to allmusic, are "scary yet sexy") are some of the most-cackhanded attempts at rock posturing yet committed to vinyl. It's really bad, I promise.

Speaking of folkie freakery here's the soundtrack to possibly the UK's greatest horror film, The Wicker Man (1973) (the only rival to The Wicker Man for the UK horror crown is the awesome Blood on Satan's Claw which mines similar material). The Wicker Man soundtrack was overseen by New Yorker Paul Giovanni, but is really mostly the work of obscure UK folk outfit Magnet, and is suitably unnerving, off-beat and spooky. I don't think it was ever given an official release as such and was put out by indie labels many years after the film's release, and the vinyl issue that I've got breaks the material into two distinct sides, the first being the fuller songs and the second being the incidental music. It's all proto freak-folk of the highest order throughout and you can hear where pretty much all of the 2000's freak-folk scene got their ideas. While Espers have tried hard to make out that it was Lubos Fiser's work on Valerie and Her Week of Wonders that inspired them, that's clearly nonsense as their records are nothing like Fiser's and are too genetically identical to The Wicker Man for it to be ignored. In any event the songs on the first side have spooky reed instruments winding their wobbly way through the acoustic guitar and vocal pieces, with the over-riding sexual impetus of the lyrics matching the same theme of the film perfectly. It all sounds suitably pagan and disconcerting, it's all entirely appropriate and you can easily imagine this stuff being played while nutty heathen rites are being performed. We've got the frightening children's round of 'Maypole', the blisteringly erotic yearning of 'Willow's Song', the bar-room filth of 'Landlord's Daughter', all of which bring the scenes in the film vividly back to mind. The incidental music on the second side is in some ways more interesting, because it really brings out the essential spookiness of this stuff, most of it being traditional music adapted for the film. There's a really deeply unsettling feel to a lot of it which chimes absolutely with the film's theme of the distance between cultures over time and although it seems silly to think about paganism as something potentially horrifying, The Wicker Man and its soundtrack demonstrate that our innate fears about collective behaviour are exercised through our fear of the past.

Here comes one that I would slate without mercy were it not for my own past. I remember being in Arles in the south of France in the blistering summer of 1988, about a month after the release of the Gipsy Kings' breakthrough single 'Bamboleo'. In the centre of Arles is a spectacular Roman amphitheatre and one night we were in town and heard, clear as day, the Gipsy Kings performing inside. It was truly an amazing evening, incredibly romantic, with the townsfolk all gathered in and around the amphitheatre going mad for the Gipsy Kings, the town beautifully lit up on a sweltering night, scorpions and foxes darting around and this faux-traditional music. It really was great. Obviously the Gipsy Kings debut album (and 7" 'Djobi Djoba' which I also bought) is pretty daft and a little silly sounding now, and the idea that it caught on so wildly with the proto Womad crowd shows, I suppose, that it wasn't any good, but I'm not going to slag it off, so there.

Girls Against Boys were making their finest work at the same time as the Afghan Whigs and although the Whigs were and have always been markedly better, there was a shared sense of urgency, a similarly misanthropic take on relationships and a musical brittleness in common. Listening to House of Girls Against Boys (1996) now it's surprising both how good the songs are and how dated the sound of it is. The whole thing starts with some brilliant, vicious bit of slicing guitar work on 'Super-Fire' and the jolting 'Click Click', and these two set the tone for the juddering, halting structures of the songs. The entire album is a close, claustrophobic rock record which, although never quite getting to the psychic depths that Greg Dulli can reach, is a bleak, black exercise in rock dynamics. Even when it slows down, it does so only in order to become even more dark and laden with foreboding (the grim 'Life in Pink' for instance), and the jagged rock songs are if anything a respite from the grim atmospherics. There's a kind of evil lounge rock on 'TheKindaMzkYouLike', which goes to pains to recreate the Afghan Whigs style, with an added pop backbeat, and 'Cash Machine' is a grinding, less violent kind of Big Black number. It's a really good album and although its production style means that you could probably guess which year it was made in without any difficulty, it's got some superb songs and an impressive attitude.

You know how Vampire Weekend weren't actually any good? If you can imagine what they might sound like if they were in fact really great, then you've imagined Givers. Their song 'Up Up Up' became a minor thing thanks to being included on the soundtrack to some stupid football computer game, (and horrifyingly was also used in an episode of Glee I believe) but forget the computer game (and particularly forget about Glee), focus on the tune, it's a quite brilliant explosion of bright, frantic pop music at its absolute finest, a rainbow of jittery "afro" guitar riffs, percussive drive and jaunty dual vocals. It's a brilliant song and although it's the most immediate on their album In Light (2011), it's still demonstrative of their style throughout. I saw them play at last year's Field Day and they were really great, energetic in the best possible way, really exciting. Where Vampire Weekend seemed to think that there was something quite amazing about being white and playing guitar riffs that sound a little bit like African riffing, Givers use the same techniques but blend them into a much bigger and way, way more impressive tapestry of sounds and styles (and don't feel the need to refer to it in interviews and their own lyrics). Givers are also much more technically interesting, forming songs from the ground up and letting them grow outwards, often ending up in very different places to where they started. 'Meantime' is a great, multi-part pop song with fantastically propulsive percussion and typically charming and enlivening vocal interplay between Tiffany Lamson (whose percussion playing is a joy to watch) and Taylor Guarisco, and 'Saw You First' is a beautifully laid-back ramble through melody, and the album is full of songs of the same calibre. There are some tunes that don't quite work (the restless 'Ripe' is a bit forgettable) but on the whole the album is a great, uplifting first outing.

Finally it's the glam racket of Glass Candy's debut Love Love Love (2003). I think that we're all supposed to love Glass Candy now but the only thing to recommend Love Love Love is the excellent gatefold sleeve. Personally I think it's a terrible record, lazy, boring and self-indulgent without the good grace to be over the top. It's an attempt at being louche in a kind of Bowie by Can kind of way and it's such an inept failure that I'm absolutely mystified as to what it is that we're supposed to be pretending to see in it. Behind the ghastly shrieking vocals (which, according to allmusic, are "scary yet sexy") are some of the most-cackhanded attempts at rock posturing yet committed to vinyl. It's really bad, I promise.

Friday 1 February 2013

LaRM day 176 (Mauro Gioia-Bebel Gilberto)

(Before starting here I should point out the alphabetical mix-up that starts this section off is because I had for ages thought the guy's name was Mauro Giaio and only realised once I'd started writing the below. Doh.)

Handsome Italian chanteur Mauro Gioia released an album in 2008 which takes soundtrack work by the legendary movie composer Nino Rota and turns it into a selection of classy easy listening pop songs, with guest appearances by all kinds of like-minded singers from the great (Ute Lemper) to the dreadful (Sharleen Spiteri). It's all great fun, loaded with swining music-hall stuff to torch song ballads and most genre appropriate stuff in between. Gioia has a decent, relatively forgettable mid-range voice, which is actually perfect for this sort of thing and he obviously went into the whole project with a ton of brio because he makes sure the whole affair is a lively, cheerful business, camp enough to be great fun without overdoing it. With a solid background in Neapolitan theatricality it's no surprise that he managed to make the record so entertaining without being too kitschy and although a lot of the material doesn't really translate that well, cross-culturally speaking, it doesn't matter remotely because it's all such rollicking silliness.

Giant Sand's first two albums, Valley of Rain (1985) and Ballad of a Thin Line Man (1986) don't resemble the sound of the band that people are more familiar with at all. Instead of the idiosyncratic dust-blown atmospheric desert rock that they're known for, these two albums are instead a kind of ramshackle jangle-rock, with chiming guitars and pounding drums hidden in the mix. If anything these records sound like an American version of the early Go-Betweens records (listen to the title track of Valley of Rain and you'll see what I mean pretty clearly). It's nice stuff, raucous and lively, brittle and anxious, but what's difficult about it is that a lot of other bands were still making these sort of records a lot better (the Rain Parade for instance were doing a much better job). There's some decent stuff on these two albums, certainly, and there are indications of the direction that the band would eventually take, but they sit quite well next to the first American Music Club album, in that they're all claustrophobically produced records which suggest much more promise to come than they actually deliver themselves.

By 2000 the elliptical Giant Sand sound was pretty much consolidated, with acoustic guitars, sun-scorched atmospherics and Howe Gelb's resigned vocals, together with Calexico's superb rhythm backing, and that sound has rarely been better used than on 2000's Chore of Enchantment LP. In keeping with other Giant Sand releases around the same time, Chore of Enchantment is unpredictable, all over the map and hard to keep a handle on, but it's punctuated by so many lovely tunes that its wilful eclecticism never grates. 'Shiver' is a real charm for instance, with Juliana Hatfield's backing vocals complementing Gelb's take it or leave it delivery nicely. 'Raw' and 'Well Dusted' are similarly graceful, and although there are moments when the album seems to be wandering into cul-de-sacs, it always pulls around in time with another fine tune. If anything, despite it's stylistic freewheeling, Chore of Enchantment is actually one of Gelb's most focussed pieces of work, in that it never loses sight of its essential character and stays true to a spirit of down-home experimentalism with enough melody to always be utterly engaging. As such it's also a record that truly rewards attention but can also provide perfect background, with its gentle, elegaic, end of a baking hot day mood.

After her songs and shows with Stan Getz, Astrud Gilberto was given the opportunity to make her own records, starting with 1965's The Astrud Gilberto Album. Any fears that her wobbly, uneven voice wouldn't be able to sustain the charm or carry an album's worth of material are put to rest by The Astrud Gilberto Album. It's a gorgeous summer day of a record, bossa and samba at its easiest and most artfully tasteful, while avoiding kitsch entirely and staying at the very finest end of what was to become the easy listening market. Apart from the unintentional stalker's manifesto lyrics of 'Once I Loved' it's all hearts and flowers, with only the occasional melancholy moment for colour, and every song is a breezy delight. Loads of the material became bossa standards. including the wonderfully slinky 'Agua de Beber', the two step jazz of 'How Insenstive', the lighter than air 'Dindi', and it's all great stuff and although in some ways its smoothness has made it prime fodder for brain-dead marketers to use in their shit adverts, that shouldn't detract from its inherent loveliness.

The follow-up, The Shadow of Your Smile (1965) tries to expand the scope of Gilberto's musical palette, by adding in some bossa readings of more straight pop to try and secure her place in the American market, but for the most part when she strays from the strict bossa template things go a bit awry. The version of the title track is a bit insipid and there's a pretty hopeless version of 'Fly Me to the Moon', along with a couple of other failures. It's a shame because when the album works, it works really well. The boulevard stroll of 'Aruanda (Take Me To)' is wonderful, the string drenched 'The Gentle Rain' is delicately precious, and 'Tristeza' is a heartbreaker. Overall the album is too uneven to really qualify as a success and the limitations of Gilberto's untrained voice are made all too plain too often throughout it, but when it flies, it really soars.

Even more of a game of two halves is 1966's Beach Samba, which has awful trite nonsense like 'A Banda' nestled up to truly wonderful songs like the absolutely perfect cover of Tim Hardin's 'Misty Roses', and for every beautiful 'My Foolish Heart' is a clumsy 'I Had the Craziest Dream'. Unlike The Shadow of Your Smile though, even when Beach Samba slips up Gilberto never sounds anything other than utterly charming and any problems with her voice are easily smoothed over by the lovely arrangements and the innate personality that she delivers all the material with. The album does go to show that a lot of the time Gilberto was only as strong as the musicians and arrangers that she worked with, but when those musicians and arrangers were sympathetic even the duds sound like triumphs. Even so, you do need a strong stomach to cope with the insanely saccharine cover of the Lovin' Spoonful's 'You Didn't Have to Be So Nice' that she sings with her six year old son...

It's all a matter of taste I suppose but when comparing the luminous work of Gilberto and the Hammond organ bossa frenzy of the other superstar of the genre in the US, Walter Wanderley, I can't help but feel that there's something so intrinsically naff about Wanderley's penny cinema organ stylings that the idea of putting the two together, although perfectly understandable at the time, now seems like asking Ingmar Bergman to make a movie starring Norman Wisdom. The album that Gilberto and Wanderley made together, 1967's A Certain Smile, A Certain Sadness, is in no way an unmitigated disaster, and there are some great arrangements of some samba greats ('Here's That Rainy Day' and 'So Nice' are really good) but you can't get away from the fact that for once a Gilberto album really would sit happily next to James Last in a suburban grandmother's record collection, and that's a disaster because Gilberto was worth so much more than that.

And so finally we have a bit more bossa but much more modern with the daughter of Astrud's first husband Joao, Bebel Gilberto and her debut solo album Tanto Tempo (2000). It's a very contemporary, slick and technically precise version of bossa, very different from the organic studio fun of the 1960's take, but that's not to say that it isn't successful. It's super-relaxed and a lot of it sounds almost tailor-made for Grey's Anatomy-type TV show soundtracks, but while that should be an insult, for once it's simply because it's unobtrusive. There's a lot of stuff going on here and occasionally there are some surprisingly odd things going on, the phased vocal tracks on the subtle 'August Day Song' aren't a million miles away from Juana Molina's challenging experimentalism and although could never accuse anything on Tanto Tempo of being challenging it is prepared to try things out. Gilberto's gently earthy voice is quietly impressive and the fusion of understatedly bossa acoustic guitar figures and electronics works surprisingly well throughout the album. Of course, this being a Gilberto's debut album she couldn't possibly get away with not covering one of the big, big samba numbers and so 'So Nice' gets a working over and it's a lovely and unshowy attempt at updating a worn out standard, and demonstrates the degree to which Bebel Gilberto really does get the fine line between the requirements of the genre and the need to keep up to date. It may not be the kind of album to get excited about but it's certainly the kind of album to be sure to have to hand.

Handsome Italian chanteur Mauro Gioia released an album in 2008 which takes soundtrack work by the legendary movie composer Nino Rota and turns it into a selection of classy easy listening pop songs, with guest appearances by all kinds of like-minded singers from the great (Ute Lemper) to the dreadful (Sharleen Spiteri). It's all great fun, loaded with swining music-hall stuff to torch song ballads and most genre appropriate stuff in between. Gioia has a decent, relatively forgettable mid-range voice, which is actually perfect for this sort of thing and he obviously went into the whole project with a ton of brio because he makes sure the whole affair is a lively, cheerful business, camp enough to be great fun without overdoing it. With a solid background in Neapolitan theatricality it's no surprise that he managed to make the record so entertaining without being too kitschy and although a lot of the material doesn't really translate that well, cross-culturally speaking, it doesn't matter remotely because it's all such rollicking silliness.

Giant Sand's first two albums, Valley of Rain (1985) and Ballad of a Thin Line Man (1986) don't resemble the sound of the band that people are more familiar with at all. Instead of the idiosyncratic dust-blown atmospheric desert rock that they're known for, these two albums are instead a kind of ramshackle jangle-rock, with chiming guitars and pounding drums hidden in the mix. If anything these records sound like an American version of the early Go-Betweens records (listen to the title track of Valley of Rain and you'll see what I mean pretty clearly). It's nice stuff, raucous and lively, brittle and anxious, but what's difficult about it is that a lot of other bands were still making these sort of records a lot better (the Rain Parade for instance were doing a much better job). There's some decent stuff on these two albums, certainly, and there are indications of the direction that the band would eventually take, but they sit quite well next to the first American Music Club album, in that they're all claustrophobically produced records which suggest much more promise to come than they actually deliver themselves.

By 2000 the elliptical Giant Sand sound was pretty much consolidated, with acoustic guitars, sun-scorched atmospherics and Howe Gelb's resigned vocals, together with Calexico's superb rhythm backing, and that sound has rarely been better used than on 2000's Chore of Enchantment LP. In keeping with other Giant Sand releases around the same time, Chore of Enchantment is unpredictable, all over the map and hard to keep a handle on, but it's punctuated by so many lovely tunes that its wilful eclecticism never grates. 'Shiver' is a real charm for instance, with Juliana Hatfield's backing vocals complementing Gelb's take it or leave it delivery nicely. 'Raw' and 'Well Dusted' are similarly graceful, and although there are moments when the album seems to be wandering into cul-de-sacs, it always pulls around in time with another fine tune. If anything, despite it's stylistic freewheeling, Chore of Enchantment is actually one of Gelb's most focussed pieces of work, in that it never loses sight of its essential character and stays true to a spirit of down-home experimentalism with enough melody to always be utterly engaging. As such it's also a record that truly rewards attention but can also provide perfect background, with its gentle, elegaic, end of a baking hot day mood.

After her songs and shows with Stan Getz, Astrud Gilberto was given the opportunity to make her own records, starting with 1965's The Astrud Gilberto Album. Any fears that her wobbly, uneven voice wouldn't be able to sustain the charm or carry an album's worth of material are put to rest by The Astrud Gilberto Album. It's a gorgeous summer day of a record, bossa and samba at its easiest and most artfully tasteful, while avoiding kitsch entirely and staying at the very finest end of what was to become the easy listening market. Apart from the unintentional stalker's manifesto lyrics of 'Once I Loved' it's all hearts and flowers, with only the occasional melancholy moment for colour, and every song is a breezy delight. Loads of the material became bossa standards. including the wonderfully slinky 'Agua de Beber', the two step jazz of 'How Insenstive', the lighter than air 'Dindi', and it's all great stuff and although in some ways its smoothness has made it prime fodder for brain-dead marketers to use in their shit adverts, that shouldn't detract from its inherent loveliness.

The follow-up, The Shadow of Your Smile (1965) tries to expand the scope of Gilberto's musical palette, by adding in some bossa readings of more straight pop to try and secure her place in the American market, but for the most part when she strays from the strict bossa template things go a bit awry. The version of the title track is a bit insipid and there's a pretty hopeless version of 'Fly Me to the Moon', along with a couple of other failures. It's a shame because when the album works, it works really well. The boulevard stroll of 'Aruanda (Take Me To)' is wonderful, the string drenched 'The Gentle Rain' is delicately precious, and 'Tristeza' is a heartbreaker. Overall the album is too uneven to really qualify as a success and the limitations of Gilberto's untrained voice are made all too plain too often throughout it, but when it flies, it really soars.

Even more of a game of two halves is 1966's Beach Samba, which has awful trite nonsense like 'A Banda' nestled up to truly wonderful songs like the absolutely perfect cover of Tim Hardin's 'Misty Roses', and for every beautiful 'My Foolish Heart' is a clumsy 'I Had the Craziest Dream'. Unlike The Shadow of Your Smile though, even when Beach Samba slips up Gilberto never sounds anything other than utterly charming and any problems with her voice are easily smoothed over by the lovely arrangements and the innate personality that she delivers all the material with. The album does go to show that a lot of the time Gilberto was only as strong as the musicians and arrangers that she worked with, but when those musicians and arrangers were sympathetic even the duds sound like triumphs. Even so, you do need a strong stomach to cope with the insanely saccharine cover of the Lovin' Spoonful's 'You Didn't Have to Be So Nice' that she sings with her six year old son...

It's all a matter of taste I suppose but when comparing the luminous work of Gilberto and the Hammond organ bossa frenzy of the other superstar of the genre in the US, Walter Wanderley, I can't help but feel that there's something so intrinsically naff about Wanderley's penny cinema organ stylings that the idea of putting the two together, although perfectly understandable at the time, now seems like asking Ingmar Bergman to make a movie starring Norman Wisdom. The album that Gilberto and Wanderley made together, 1967's A Certain Smile, A Certain Sadness, is in no way an unmitigated disaster, and there are some great arrangements of some samba greats ('Here's That Rainy Day' and 'So Nice' are really good) but you can't get away from the fact that for once a Gilberto album really would sit happily next to James Last in a suburban grandmother's record collection, and that's a disaster because Gilberto was worth so much more than that.