With Little Feat taking an adventurous turn by incorporating jazz fusion elements into their R&B and southern boogie, leader Lowell George chose to go back to basics for his 1979 solo album, Thanks I'll Eat It Here. Not particularly pleased with the direction that Bill Payne and Paul Barrere were taking Little Feat, the solo album was an opportunity for the ailing George to take a look back and make a record that in a relaxing rather than antagonistic atmosphere. And relaxed really is the word for Thanks I'll Eat It Here. A smoother piece of countrified, bluesy R&B it's hard to imagine, with covers of 'What Do You Want the Girl To Do' and 'I Can't Stand the Rain' sounding like the coolest things George had turned his hand to in a good five years. There's the sprightly Mexicana of 'Cheek to Cheek', the funky 'Honest Man', the Southern blues-riffing on a version of Little Feat's own 'Two Trains'. There's only one bad moment on Thanks I'll Eat It Here and that's down to the peculiar inclusion of Jimmy Webb's silly 'Himmler's Ring', which sticks out like a sore thumb on the album. But that's the only dip in quality as the rest of the album is great, a laid-back outing which just feels good throughout. And it's got one of George's finest and most effecting tunes, the charmingly low-key love song '20 Million Things'.

During the brief indie-world domination enjoyed by bands in the Elephant 6 collective, one of the few who were pretty much ignored by everybody was the Gerbils, who released a couple of albums, the first of which was Are You Sleepy? (1998). The title is a fairly nice way of referring to a lot of the Elephant 6 sound, a woozy, dozy indie shamble that charms and infuriates in equal measure. Are You Sleepy? has a handful of fairly standard ramshackle indie tunes which ramble around in a cheerful manner, and apart from the pointless sound experiment of 'Wet Host' it's all amiable enough. The real problem with it I suppose is that other Elephant 6 bands, particularly Marshmallow Coast and Apples in Stereo, were doing this stuff much more effectively and with much more character. There are some good pop songs ('Is She Fiona' is great and 'Glue' is a good effort at a more serious sound) but it's not enough to lift the album out of the second tier of the Elephant 6 roster.

Emo! The first two albums by the Get Up Kids, Four Minute Mile (1997) and Something To Write Home About (1999) were for better or worse pretty influential records. They effectively launched the careers of a million other spritely emo and pop acts from Sunday's Best and Jimmy Eat World to Blink 182 and sodding Busted and everything in between and although the whole second wave of emo now sounds appallingly stilted and corporate, there was something sparky in there, particularly in the Get Up Kids lively efforts at sounding "real". Of all those indie-emo acts I don't mind the Get Up Kids records, I think that the heartfelt college kid yearning nonsense was all pretty genuinely meant and led to some records that sound warm and engaged. It's all silly, adolescent and pretty weak in truth, but I don't mind it at all and it kind of reminds me of a fun time too so I have to cut it all some slack for that reason alone. Four Minute Mile and Something To Write Home About are decent enough emo records, nothing on them particularly stands out but it's more the mood, the legitimising of indie-kid feeling, that struck such a chord, especially in the US and although the albums themselves are fairly forgettable they're still surprisingly appealing records.

There's a good chance that the reason I'm prepared to be forgiving of the Get Up Kids is because Pitchfork hated them so very, very much and anyone that Pitchfork goes out their way to slag off I'll likely defend because most of the writers for Pitchfork are utter morons. However, nobody but nobody could defend most of the material on their third album, the rarities and B-sides collection called Eudora (2001). This stuff is appalling. Particularly noxious are the many cover versions the Get Up Kids recorded and which are, without exception, dreadful. They mercilessly desecrate, amongst others, the Pixies 'Alec Eiffel', the Replacements' 'Beer for Breakfast', Dave Bovril's 'Suffragette City' and New Order's 'Regret', and this sacrilege is really quite horrible to listen to. The rest of it is even limper original material, with a couple of minor saving graces (a decent version of Four Minute Mile highlight 'I'm a Loner Dottie, a Rebel' and 'Anne Arbour') and there's really no excuse for it.

And so on to something of a very different hue, the glorious majesty of Getz au GoGo, a live document from the height of Stan Getz's and Astrud Gilberto's collaborative period, recorded at two shows in 1964 and released the following year. By 1964 saxophonist Getz was coming to the end of his "bossa nova period" (having been an key part of the global popularisation of bossa) and the two shows at the Cafe au GoGo in Greenwich Village capture his quartet at their absolute best, and Gilberto's presence just adds beautifully to the graceful performances. Interestingly most of the material is not bossa but is American, but Getz's quartet plays it all out as bossa-lite and Gilberto's ever wonderful voice ensures the Brazilian feel throughout. Every tune is superb, and out of a near perfect set particular highlights are samba standards 'It Might as Well Be Spring' and 'Corcovado', a great bossa reading of 'Summertime' from Porgy & Bess (which has some fine interplay between Getz, Kenny Burrell, Chuck Israel and Gary Burton), an utterly charming version of 'One Note Samba' and a lovely little bit of messing about on 'The Telephone Song', at the conclusion of which Gilberto lets out a heart-melting laugh.

And so to finish it's 70 minutes of Japan's finest exponents of free-form psychedelic jazz freakouts, Ghost, with their 2004 album Hypnotic Underworld. The opening 24 minutes are taken up with the four movement title track, which begins with almost quarter of an hour of spooky jazzed out atmospherics with distant wailing sax, bubbling bass and windy electronic noise. This mutates into 7 minutes of gradually building fuzz-bass, eastern sax figures and frenzied piano bashing before collapsing into a total psychedelic rock monster. The rest of the album is not quite up to the same standard as the title track but there's a lovely psych cover of Dutch prog rock act Earth & Fire's 'Hazy Paradise' and 'Piper' is a great psych rock piece (the title presumably complementing the brilliantly mutated cover version of Syd Barrett's 'Dominoes' which closes the album). Overall it's an unusually accessible experimental psych album, never relying too heavily on abstraction or massive guitar workouts or trippy nonsense, instead always keeping an ear on melody (especially on the lovely almost straight rock song 'Feed') and keeping in control. It's possibly a little overlong, but that's not unusual for albums that work themselves out in this sort of way, and for the majority of its running time Hypnotic Underworld is really great stuff.

Thursday, 31 January 2013

Tuesday, 29 January 2013

LaRM day 174 (Genesis-Bobbie Gentry)

1976's second Genesis album, Wind & Wuthering, is similar to A Trick of the Tail but is not as immediate and effectively acts as the transitional album betraying a determination to move towards more of a pop market. It's no surprise that guitarist Steve Hackett left after Wind & Wuthering, his leaning being much more towards the prog end of the scale will have meant that the direction the band were moving in wouldn't have been to his taste. There are some saving graces on the album, opener 'Eleventh Earl of Mar' continues A Trick of the Tail's extended pastoral progisms, but for the most part it's a fairly sappy exercise, with sloppy, soppy pop songs like the ghastly 'Your Own Special Way' and the tedious 10-minute trudge of 'One for the Vine'. The OK stuff is perfectly fine but the duds are terrible and the album really suffers from the band not choosing one style over the other.

The decision was pretty much made following Hackett's departure, and the songs on 1978's And Then There Were Three are pop/rock songs with a touch of prog excess. As far as the band's prog fanbase were concerned this was pretty much the ultimate betrayal but for the world at large it was the Collins/Banks/Rutherford line-up that would make records to fit the popular taste. A lot of And Then There Were Three works really well, giving the melodic touches precedence over the excessive musicality, and there are some fine songs. 'Snowbound' is a lovely slow-burner, 'Follow You Follow Me' is a great straightforward pop song, and 'Deep in the Motherlode' makes a decent case for moving prog into a more traditional rock song structure. There are some cheesy results out of the pop over prog approach - 'Undertow', despite a supremely tight structure, is fairly grim, and 'Ballad of Big' is just dreadful. They hadn't ditched the prog entirely, and opener 'Down and Out' nicely harks back to the brittle excess of The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway, and 'The Lady Lies', while awful, has some jazzy prog chops and tricky time signatures. It's a ropey album all told, but a lot better than Wind & Wuthering and because it was clear that the trio had made a pretty clear decision to move into a more pop/rock territory it feels a lot more confident, and the handful of good bits are really great.

.jpg)

A couple of years later (after marriage crises and solo album crises) Collins, Banks and Rutherford reconvened to make 1980's Duke. Showing a proclivity to retain their prog credentials, they pieced together a thirty minute concept suite about an everyman figure called Albert. When it came to sequencing the album though they decided not to alienate their now sizeable mainstream audience and split the piece into six distinct songs, interspersed with other stand-alone tunes. As a result Duke sounds like a relatively straight pop/rock album and although opener 'Behind the Lines' kicks off with a rocking prog workout, it soon settles into a verse/chorus arrangement (it does still retain some serious Gabriel era atmosphere amongst the popism though). And there's the tone of the whole album, whenever it threatens to get too prog, it kicks back vehemently with some strident pop melody and on the whole, even more than And Then There Were Three, Duke is a pop album with prog flashes. The difficulty I have with Duke is that it's another one of those albums that looms so large over my memory of growing up that I can't hear anything wrong with it. I know that for all prog fans it's an absolute calamity and for most pop fans it's just rubbish, but it's a near perfect album for me, in the same way that Jeff Wayne's War of the Worlds is. I know it's probably absolutely appalling, but I just can't hear it. So, my view of Duke is prejudiced, but to my ears, it's the only point at which Genesis' mutation into a pop/rock act really worked perfectly. The out and out pop songs ('Turn It On Again', 'Misunderstanding') are great; the bold, dark rock songs ('Duchess', 'Man of Our Times') are great; the prog-lite numbers ('Behind the Lines', the closing parts of the so called "Duke suite") are great. Pretty much all of Duke is great, and although it was the opening salvo of what was to become a cloying and horribly "adult" form of rock that the band would go on to make, on it's own Duke is a fine album. Although I should just mention that the song 'Please Don't Ask' absolutely stinks.

Now we should leave Genesis at this point but because all of the preceding albums I've only got on vinyl I thought it might be a good idea to by the CD of The Platinum Collection (2004) which covers pretty much their entire career, which of course means covering all of the terrible albums that they made in the 80's and 90's as well as the brilliant ones they made in the 70's. So, what's here? Well, we get off to a decent start with one song from 1970's Trespass. 'Knife' is certainly the highlight of that album and is a great bit of prog grandstanding from the whole band, with Gabriel in full flow. We'll skip over everything already covered, which brings us to the material from 1981's Abacab and 1983's Genesis albums. Both of these records consolidated the absolute move from prog to pop and are half OK and half utterly dismal. Only the title track and 'Keep It Dark' from Abacab make it onto the Platinum Collection and they're both great rock songs from an alright album. By contrast the whole first two thirds of the Genesis album makes an appearance and it's fairly rough. 'Mama' is dark and gloomy but daft (Collins' mad "ha-ha" noise is really silly), 'Home by the Sea' is rubbish and 'Illegal Alien' is inexplicable. 'That's All' is OK though I guess. Then it's all the third-rate garbage from the Invisible Touch, We Can't Dance and Calling All Stations albums, and that's all not worth discussing.

And so on to possibly the wettest album ever made, and a superb reminder of one of the best weekends of my life, it's The Green Fields of Foreverland (1999) by The Gentle Waves. The Gentle Waves was basically Belle & Sebastian's Isobel Campbell doing her own unbelievably sappy thing and it's as limp as old lettuce. You could claim that it's charming and you could claim that it has a gossamer grace, but the thing is, it is in truth utterly insipid. At the Bowlie Weekender it was an album on heavy rotation in people's chalets and was one of the reasons why Patrick, Alex and myself went Zeke mad in the middle of the night. It wasn't a nice thing to do, it wasn't charming, in fact it was pretty tossy of us, but to be honest I think it's fair to say that we were driven to it by the soppy, floppy haired nonsense that was going on around us. If any record cries out to be challenged by some vicious speed-punk it's the wet rag of The Green Fields of Foreverland. Now, I'm not going to claim that it's a bad record, it isn't by any stretch, it's actually proof of Campbell's deft way with a light indie melody, but my God, it fulfils every last jock stereotype of the indie kid, and for being so stupid as to make those horrible stereotypes true it deserves to be consigned to the dustbin of indie history.

The mighty Bobbie Gentry stands as a good contrast to Isabel Campbell. She found fame quickly and stridently, made the most of it and chose to disappear completely at the height of her success. A superb talent, a fantastic songwriter and a fascinating presence, Gentry made a handful of absolutely fabulous records. As a country artist Gentry was too oblique, as a pop artist too rough, and as a rock artist too deeply entrenched in her Chickasaw County Southern mythology, and consequently she carved out a fairly unique position for herself. Her second album, The Delta Sweete (1968) is, like her debut, a record so steeped in her environment as to make it almost palpable when listening to the album. It's a record absolutely about a sense of place, a definitive statement about experience as lived not as expressed and it cuts right to the core of what made Gentry such a unique talent - she talked about her experience, she didn't particularly try to embellish it for the sake of the audience. These songs are about southern families, shanties and shacks, poverty, childhood and mystery and as such reek of authenticity while still being fantastic pop songs. Gentry's ironic, drawling, smoky delivery just adds more flavour to the songs and her strange picking and up-strum guitar playing is fascinating. The original of the superb 'Mornin' Glory' appears on The Delta Sweete, at it's woozy, drowsy best, and there are scores of other great tunes. The hand-clapping Southern chant of 'Reunion' creates the sense of a rowdy, full family room brilliantly and 'Sermon' puts the listener in the position of the preacher's audience. It's all brilliant, evocative stuff and deserves to be much better known.

The Bobbie Gentry & Glen Campbell album (her third of 1968) is a sterling collection of songs, marking out a loose, casual and utterly engaging collaboration, with both Gentry and Campbell playing off each other in such a charmingly relaxed fashion that you can only imagine what fun it was to make the record. Gentry's 'Mornin' Glory' gets a jaunty, cheerful working over (as opposed to the blurry-eyed original) and her smoky, sweet voice blends with Campbell's perfectly throughout the record. There are fine versions of 'Gentle On My Mind' and 'Let It Be Me', but there are a couple of low spots in versions of 'Little Green Apples' and a bizarre choice of Simon & Garfunkel's 'Canticle'. For the most part it's an easy pop-country album, but between them Gentry and Campbell make the whole thing so much more.

Not only was Gentry a singular musical voice, she was also one of the first female country artists to produce her own records and, although this has never been confirmed, painted the brilliant, sultry self-portraits for the covers of later albums Fancy and Patchwork. But we'll probably never know, so uncompromisingly and successfully has she demanded to be left alone since quitting showbusiness in the mid-1970's. The last bit of Gentry for us is the 2000 compilation Ode to Bobbie Gentry, covering her output between 1967 and 1971. Her debut single 'Ode to Billie Joe' still sounds other-worldly with it's skeletal acoustic guitar and strings telling a spookily depressing Carson McCullers-ish tale. It's a fantastic song, an amazing calling card, but really only set out the basics of what Gentry was capable of. For the Fancy and Touch 'Em with Love albums Gentry was advised to focus on covers and apart from 'Fancy' itself, which is one of her finest, and most depressing, songs, her originals aren't included on Ode to Bobbie Gentry. Instead lots of the covers are included, and despite not having her peculiar edge of authenticity, they're big, showy and great cover versions. There are really two clear sides to Gentry, which the compilation brings out - the Vegas show style which is big and ballsy, and the denser, more personal Southern tales. The personal stuff is better, but there's very little that Gentry touched that isn't superb. Even 'In the Ghetto', and that's saying something.

Monday, 28 January 2013

LaRM day 173 (Genesis)

Come and touch me, why don't you touch me? Well, one look at Peter Gabriel in his creepy old man mask would answer the question, but there's no denying the theatrically absurd brilliance of much of Genesis' breakout album, their third, Nursery Cryme (1971). Nursery Cryme is absolute and unadulterated proggus maximus. Prog may have got cracking in the late 1960's and Yes may have churned out some extremely complicated prog workouts, but Nursery Cryme was the point at which everything proggish coalesced into a completely hermetically sealed, and quite specifically English, context. Not only is the music ridiculously complex, but thematically Gabriel had introduced linking stories and ideas between the songs to create, not a concept album, but a pastorally quaint concept entire, and as a result Nursery Cryme sounds like a song cycle. There is a skewed version of subtlety at work as well. Where Yes were making laughably overblown records, Nursery Cryme is strangely intimate, and despite it's convoluted song structures, has time for some genuine melody and even a low-key pop sensibility shows up from time to time. That's doesn't stop 10 minute opener 'The Musical Box' from being a grandstander, flitting about all over the show. It's a fantastic piece of work, and shows off new Genesis recruit Phil Collins' hugely important impact on the band. Similarly over the top is 'Return of the Giant Hogweed', a rolling, thundering slice of multi-movement prog in which Tony Banks tries to outdo Keith Emerson for idiotically dramatic keyboard work. It's great stuff, but to be honest 'The Musical Box', 'Return of the Giant Hogweed' and album closer 'The Fountain of Salmacis' (which has lovely little flashes of charming vocal melody from Gabriel) are the real highlights of the album, the other five shorter songs are pretty forgettable (or, in the case of 'Harold the Barrel', terrible). 'Seven Stones' is OK but relies too heavily on Banks' cod-classical keyboard fugues and has an uneasily sloppy chorus, 'For Absent Friends' is alright too, but suggests that they shouldn't have let Collins start writing songs so early after joining the band, and 'Harlequin' too crassly betrays the band's debts to Pink Floyd. There are problems with Nursery Cryme, but nevertheless it really was the definitive starting point for a totally unified sense of what British prog was and could be.

Fourth album Foxtrot (1972) is often cited as the band's best, mainly because of the 23-minute opus 'Supper's Ready'. The album gets off to a flying start with the rocking 'Watcher of the Skies' which is built on a brilliant Mellotron noise and juddering keyboard and guitar thuds, and a brilliant lyric and vocal line from Gabriel. Things get a bit sappier with the much less convincing 'Time Table', which strangely foreshadows the easier fare that Genesis would serve up later in their post-Gabriel career. It's a shame because the dark but lively 'Watcher of the Skies' sets you up for much more entertaining stuff than 'Time Table'. Things get back on track with the churning prog of 'Get Em Out By Friday', which is another multi-movement 8-minute workout, but even so, it's not the greatest or most cohesive of Genesis' big, multi-part songs. 'Can-Utility and the Coastliners' is a fairly charming acoustic guitar based song, and 'Horizons' is a decent classical cribbing bit of prog frippery (as usual, when prog musicians want a bit of classical to riff on, Genesis turned to Bach). But, with the exception of 'Watcher of the Skies', these songs are just a padding exercise, the throwaway prelude to the main act, side two's monumental (and monumentally ridiculous) 'Supper's Ready'. 'Supper's Ready' is huge in every sense. It has six framing movements, but loads within those six and it's a patchwork quilt of ideas, both musical and lyrical, making one flowing, rolling piece of melodramatic prog, covering every conceivable theme, from childhood terrors to the formation of the world, from medieval life to ancient mythology, and although it's unspeakably daft, it's still bizarrely thrilling. Perhaps the most surprising thing about it is that it isn't ever a chore to listen to, despite being full of showy bits of soloing and unlimited excess, mainly because it never loses sight of melody and even when it's at it's most absurd, it still remembers to entertain rather than simply show off.

1973's Selling England by the Pound is a better album yet, despite having even more silly cultural allusions to a jarringly quaint Englishness. Opener 'Dancing with the Moonlit Knight' starts off with medieval guitar filigrees and ends up a blisteringly over the top rock song, complete with synthesised choir and overdriven electric guitar work from Steve Hackett which is truly daft. But once again, Gabriel's strong melodic sense runs through the song and saves it from being simply stupid prog (although Banks' squelchy keyboard solo is pretty stupid). It kind of sets the tone for the whole album too, in that thematically it appears to be reflecting on the common topic of the transition from rural English pastoralism to cultural co-option (unstatedly the US) in an urban context, and the 12-minute 'The Battle of Epping Forest', the grandiose 'Firth of Fifth' and album closer 'The Cinema Show/Aisle of Plenty' revolve around the same theme. There's a pop song (and chart "hit") in the superb 'I Know What I Like (In Your Wardrobe)', which really demonstrates just how closely Genesis were able to tie prog to pop (it's far from being a standard pop song, but the chorus is pure pop hook), and also led to Gabriel's infamous impersonation of a lawn mower in the band's live shows. The album has generally been under-appreciated, with reviews tending to focus on the obliqueness or showy silliness of the lyrics, while ignoring the tension and discomfort that lies beneath that silliness. Musically the album is less dense than the preceding albums, and although still crazily convoluted, it's really pretty accessible. There are down moments, particularly Collins' mawkish and forgettable 'More Fool Me' which is fairly ghastly, and Steve Hackett's 'After the Ordeal' is pretty pointless, but otherwise Selling England by the Pound is a great album, and a worthy precursor to the absolutely blistering slab of solid prog mayhem that was to follow.

The material on 1975's sprawling double-album The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway is musically much more precise and more direct than anything Genesis had recorded before, yet it's the densest, most impenetrable and easily the best record they ever made. It's dark, jagged, mysterious, urban, a world away from the gently satirical English pastoralism of their previous work. The whole exercise was undertaken in an atmosphere of increasing conflict, particularly between Peter Gabriel and Tony Banks and, as is so often the way, it was this antagonism that seems to have led directly to the band making their best work. But, the fallout was to be that after one tour of the album Gabriel would leave the band in fury and under a cloud, with the rest of Genesis loudly and publicly expressing their irritation at the idea that the frontman's theatricality detracted from the music, and Gabriel retorting that they wouldn't amount to much without him. In any event, The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway is a prog record through and through, yet only three of its twenty-three songs break the 6-minute mark, it's a heads-down rock album but with spectacularly complex musical structures, and it's a pop record with no concessions made to popular taste whatsoever. As a concept album it's one of the least narratively understandable, with a tale seemingly about a Puerto Rican street punk called Rael trying to stay alive in New York, but that's pretty much all you can really get from it, because Gabriel tells his story in such pointedly oblique terms that there's little point in trying to make sense of it all. If anything, that obliqueness just makes the album all the more fascinating, and together the myriad classical references, the musical conflations and thematic numinousness makes for a really quite spectacular record. For the first time, the slower numbers sound like really great and thematically appropriate instead of the jarringly pat mis-steps they had been previously and 'The Lamia' and particularly the wonderful 'Carpet Crawlers' are superb. The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway is difficult, absurd, insanely overblown, antagonistically brainy, and, if you're prepared to accept that it's Genesis that you're listening to, it's absolutely brilliant. Now, there are many people who aren't prepared to accept that Genesis are anything other than total shit (I live with one for a start), but the thing is, sometimes you have to put your prejudices to one side and accept that you're wrong. Because The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway really is absolutely brilliant.

After Gabriel's departure there wasn't really anywhere for the band to go but backwards, and they did just that, retreating to the gentler, more obviously prog style that they had been refining prior to The Lamb. A Trick of the Tail is a decent enough prog album, but there isn't enough that really stands out, and after the previous album's outstanding bluster, A Trick of the Tail sounds like a band in retreat, and it's all a bit forgettable. There are some good outings: 'Squonk' is pretty decent winding prog, opener 'Dance on a Volcano' is pretty beefy and the title track is nice. But there are also worrying signs of what's to come with the lacklustre and silly 'Robbery, Assault and Battery' which manages to combine by-numbers prog with a second rate pop melody in its chorus. It's OK, and as a wounds-licking exercise it's absolutely fine, but it is an album that suggests that if the band wanted to keep moving forward they would need to start developing other ideas than the prog workouts they had relied on in the past.

Fourth album Foxtrot (1972) is often cited as the band's best, mainly because of the 23-minute opus 'Supper's Ready'. The album gets off to a flying start with the rocking 'Watcher of the Skies' which is built on a brilliant Mellotron noise and juddering keyboard and guitar thuds, and a brilliant lyric and vocal line from Gabriel. Things get a bit sappier with the much less convincing 'Time Table', which strangely foreshadows the easier fare that Genesis would serve up later in their post-Gabriel career. It's a shame because the dark but lively 'Watcher of the Skies' sets you up for much more entertaining stuff than 'Time Table'. Things get back on track with the churning prog of 'Get Em Out By Friday', which is another multi-movement 8-minute workout, but even so, it's not the greatest or most cohesive of Genesis' big, multi-part songs. 'Can-Utility and the Coastliners' is a fairly charming acoustic guitar based song, and 'Horizons' is a decent classical cribbing bit of prog frippery (as usual, when prog musicians want a bit of classical to riff on, Genesis turned to Bach). But, with the exception of 'Watcher of the Skies', these songs are just a padding exercise, the throwaway prelude to the main act, side two's monumental (and monumentally ridiculous) 'Supper's Ready'. 'Supper's Ready' is huge in every sense. It has six framing movements, but loads within those six and it's a patchwork quilt of ideas, both musical and lyrical, making one flowing, rolling piece of melodramatic prog, covering every conceivable theme, from childhood terrors to the formation of the world, from medieval life to ancient mythology, and although it's unspeakably daft, it's still bizarrely thrilling. Perhaps the most surprising thing about it is that it isn't ever a chore to listen to, despite being full of showy bits of soloing and unlimited excess, mainly because it never loses sight of melody and even when it's at it's most absurd, it still remembers to entertain rather than simply show off.

1973's Selling England by the Pound is a better album yet, despite having even more silly cultural allusions to a jarringly quaint Englishness. Opener 'Dancing with the Moonlit Knight' starts off with medieval guitar filigrees and ends up a blisteringly over the top rock song, complete with synthesised choir and overdriven electric guitar work from Steve Hackett which is truly daft. But once again, Gabriel's strong melodic sense runs through the song and saves it from being simply stupid prog (although Banks' squelchy keyboard solo is pretty stupid). It kind of sets the tone for the whole album too, in that thematically it appears to be reflecting on the common topic of the transition from rural English pastoralism to cultural co-option (unstatedly the US) in an urban context, and the 12-minute 'The Battle of Epping Forest', the grandiose 'Firth of Fifth' and album closer 'The Cinema Show/Aisle of Plenty' revolve around the same theme. There's a pop song (and chart "hit") in the superb 'I Know What I Like (In Your Wardrobe)', which really demonstrates just how closely Genesis were able to tie prog to pop (it's far from being a standard pop song, but the chorus is pure pop hook), and also led to Gabriel's infamous impersonation of a lawn mower in the band's live shows. The album has generally been under-appreciated, with reviews tending to focus on the obliqueness or showy silliness of the lyrics, while ignoring the tension and discomfort that lies beneath that silliness. Musically the album is less dense than the preceding albums, and although still crazily convoluted, it's really pretty accessible. There are down moments, particularly Collins' mawkish and forgettable 'More Fool Me' which is fairly ghastly, and Steve Hackett's 'After the Ordeal' is pretty pointless, but otherwise Selling England by the Pound is a great album, and a worthy precursor to the absolutely blistering slab of solid prog mayhem that was to follow.

The material on 1975's sprawling double-album The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway is musically much more precise and more direct than anything Genesis had recorded before, yet it's the densest, most impenetrable and easily the best record they ever made. It's dark, jagged, mysterious, urban, a world away from the gently satirical English pastoralism of their previous work. The whole exercise was undertaken in an atmosphere of increasing conflict, particularly between Peter Gabriel and Tony Banks and, as is so often the way, it was this antagonism that seems to have led directly to the band making their best work. But, the fallout was to be that after one tour of the album Gabriel would leave the band in fury and under a cloud, with the rest of Genesis loudly and publicly expressing their irritation at the idea that the frontman's theatricality detracted from the music, and Gabriel retorting that they wouldn't amount to much without him. In any event, The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway is a prog record through and through, yet only three of its twenty-three songs break the 6-minute mark, it's a heads-down rock album but with spectacularly complex musical structures, and it's a pop record with no concessions made to popular taste whatsoever. As a concept album it's one of the least narratively understandable, with a tale seemingly about a Puerto Rican street punk called Rael trying to stay alive in New York, but that's pretty much all you can really get from it, because Gabriel tells his story in such pointedly oblique terms that there's little point in trying to make sense of it all. If anything, that obliqueness just makes the album all the more fascinating, and together the myriad classical references, the musical conflations and thematic numinousness makes for a really quite spectacular record. For the first time, the slower numbers sound like really great and thematically appropriate instead of the jarringly pat mis-steps they had been previously and 'The Lamia' and particularly the wonderful 'Carpet Crawlers' are superb. The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway is difficult, absurd, insanely overblown, antagonistically brainy, and, if you're prepared to accept that it's Genesis that you're listening to, it's absolutely brilliant. Now, there are many people who aren't prepared to accept that Genesis are anything other than total shit (I live with one for a start), but the thing is, sometimes you have to put your prejudices to one side and accept that you're wrong. Because The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway really is absolutely brilliant.

After Gabriel's departure there wasn't really anywhere for the band to go but backwards, and they did just that, retreating to the gentler, more obviously prog style that they had been refining prior to The Lamb. A Trick of the Tail is a decent enough prog album, but there isn't enough that really stands out, and after the previous album's outstanding bluster, A Trick of the Tail sounds like a band in retreat, and it's all a bit forgettable. There are some good outings: 'Squonk' is pretty decent winding prog, opener 'Dance on a Volcano' is pretty beefy and the title track is nice. But there are also worrying signs of what's to come with the lacklustre and silly 'Robbery, Assault and Battery' which manages to combine by-numbers prog with a second rate pop melody in its chorus. It's OK, and as a wounds-licking exercise it's absolutely fine, but it is an album that suggests that if the band wanted to keep moving forward they would need to start developing other ideas than the prog workouts they had relied on in the past.

Thursday, 24 January 2013

LaRM day 172 (Rebecca Gates-Howe Gelb)

After the Spinanes sadly split up Rebecca Gates has made only the most sporadic of appearances and pretty much her last recording was 2001's mini-LP, Ruby Series. The seven songs on Ruby Series are a delicate combination of Gates' smoky, mournful voice and Tortoise's John McEntire's subtle musical experimentalism. Opener 'The Seldom Scene' is a lovely little song, with twinkling keyboards, reverbed glockenspiel and muted drums and Gates' haunting, untrained voice, gliding through the song, like a somebody drifting through an empty house. It's a beautiful, mood-setting piece, the rest of the songs on Ruby Series match the tone, and the feeling throughout the majority of the album. A cheap drum machine and wobbly guitar underpin the otherwordly glockenspiel melody on the quietly stunning 'Lure and Cast', and the spectral 'Move' relies almost solely on a melancholy occasional guitar strum, Gates' late-night voice and some indefinable electronic noises buried deep in the mix. Both songs are really quite beautiful and reflective in the least self-indulgent way possible. The centepiece of the album is probably the weakest moment, and the one in which McEntire takes over the show too obviously. Even the title, 'In a Star Orbit' doesn't really sound like Gates and the jaunty kiddie-rhythm drum machine and Gates' processed vocals don't fit the mood of the rest of the record very well. That's not to say it isn't great, it just sticks out somewhat and breaks the flow of the record. The last three songs revert to the mood of the first half though and the whole thing plays out with the lovely 'I Received a Levitation', which is a ringing, treble vocal-tracked piece of elegaic beauty and a fitting epitaph for an understated but creatively charmingly career. (Although having written that I've just read that Gates has just released a new album, 12 years after Ruby Series so not an epitaph after all, just a lovely record.)

Next up is one of the most notorious stories in pop music. The background to the release, and particularly to the title, of Marvin Gaye's 1978 album Here My Dear is uncommonly odd and unpleasant. For some years before the recording of the album the relationship between Gaye and his wife Anna Gordy had been deteriorating badly, with both accusing the other regularly of infidelity and irresponsibility and in 1975 Gordy finally filed for divorce. Gaye had been busy with his cash buying copious numbers of cars and mountains of cocaine and consequently didn't have anything like enough left to pay his alimony and child support. The answer? Agree to give Gordy half the royalties from his next album, which Gaye went into the studio to start recording in 1976 with the specific intention of making it as crap (or, in his own words, "lazy") as possible. Things didn't go according to plan and once recording started Gaye found himself pouring out all kinds of confessional stuff about the situation with the lyrics veering wildly between astonishingly vicious hatred and sentimental nostalgia, and the tunes accordingly found themselves being worked on with more and more attention to detail. The resulting album, whose title refers to the fact that pretty much any money it made was going to be given to Anna, was absolutely panned on its release but, as is so often the way, has had a monumental critical re-evaluation since, and rightly so. It's a fantastic record. It's certainly wilful, difficult, irritating, incoherent, but as a soul album, it's absolutely laced with odd, jazzy inflections, really funky breaks, and contains some of the most fascinatingly, explicitly, personal lyrics ever set out in music. When it's calm it rivals any of Gaye's other work for soulful introspection and when its dander is up it's furiously uncomfortable. 'When Did You Stop Loving Me, When Did I Stop Loving You' and 'Everybody Needs Love' are fantastic examples of Gaye's real artistry, his ability to transcend the limitations of R&B and turn it into something quite other. There are hard to take moments (the 8 minutes of 'Funky Space Reincarnation' didn't absolutely need to be included) but on the whole, in its deeply personal nature, its unpredictability and its self-determined unwillingness to abide by any preordained structure, Here My Dear as is close to art as R&B is ever going to get.

After leaving The Softies for the first time, the queen of twee Rose Melberg formed Gaze with some like-minded chums. First album Mitsumeru (1998) is another twee-pop gem, scarcely any different to any other (and certainly closer to Melberg's work in Tiger Trap than the Softies). It's got some up songs, it's got some slow songs, but they're all of the artless, clumsy, thoroughly charming librarian pop school that was all the rage for the Olympia kids in the mid to late 1990's. There are songs about jelly beans, songs with names like 'Preppy Villain' and the whole ramshackle pop fun of the exercise is infectiously endearing. As with all of Melberg's work it flirts shamelessly with being annoying but always manages to stay the right side of the line. Melberg did let down Zoe quite badly once by being something of an arse, but that's a different matter, and her records are always speccy charm personified.

Whilst overseeing the endless production line of Giant Sand albums, the ludicrously prolific Howe Gelb also finds the time to make copious albums under variations of his own name, one of which is next on the list. The Listener (2003) is one of Gelb's more accessible excursions into the oblique and focusses more heavily on his instrumental work and occasional Lou Reed impressions than the abstract desert rock and Americana that he tends to centre his records on. There are some surprisingly low-key and graceful piano tracks and piano led songs on The Listener and although it can veer directly into wanting to be Berlin (second track 'Felonious' is a prime example, even stating that it's a Lou steal) it's a delicate Sunday afternoon of an album. There are great jazzy trumpet solos and babbling bass over the indie-blues of the piano work, but this isn't rubbish like Eels bizarrely misconceived notion of how indie bands play the blues, this is the work of someone who has worked hard to really get it, to really understand how different musical forms work and why it's worth using some and discarding others. The Listener is a surprising album for Gelb partly because his work, while always shot through with a mordant sense of humour, can be furious and ragged and instead The Listener is calm, subtle, smart and smarmy, sarky and cool, it's a record that knows it should be playing in the corner of a run-down bar on a hot day, a hyper-ironic take on Ry Cooder's Texico swing.

Pretty brief today but tomorrow is going be one almighty Gabriel fest - it's a whole day of prime Genesis. PROG ON.

Next up is one of the most notorious stories in pop music. The background to the release, and particularly to the title, of Marvin Gaye's 1978 album Here My Dear is uncommonly odd and unpleasant. For some years before the recording of the album the relationship between Gaye and his wife Anna Gordy had been deteriorating badly, with both accusing the other regularly of infidelity and irresponsibility and in 1975 Gordy finally filed for divorce. Gaye had been busy with his cash buying copious numbers of cars and mountains of cocaine and consequently didn't have anything like enough left to pay his alimony and child support. The answer? Agree to give Gordy half the royalties from his next album, which Gaye went into the studio to start recording in 1976 with the specific intention of making it as crap (or, in his own words, "lazy") as possible. Things didn't go according to plan and once recording started Gaye found himself pouring out all kinds of confessional stuff about the situation with the lyrics veering wildly between astonishingly vicious hatred and sentimental nostalgia, and the tunes accordingly found themselves being worked on with more and more attention to detail. The resulting album, whose title refers to the fact that pretty much any money it made was going to be given to Anna, was absolutely panned on its release but, as is so often the way, has had a monumental critical re-evaluation since, and rightly so. It's a fantastic record. It's certainly wilful, difficult, irritating, incoherent, but as a soul album, it's absolutely laced with odd, jazzy inflections, really funky breaks, and contains some of the most fascinatingly, explicitly, personal lyrics ever set out in music. When it's calm it rivals any of Gaye's other work for soulful introspection and when its dander is up it's furiously uncomfortable. 'When Did You Stop Loving Me, When Did I Stop Loving You' and 'Everybody Needs Love' are fantastic examples of Gaye's real artistry, his ability to transcend the limitations of R&B and turn it into something quite other. There are hard to take moments (the 8 minutes of 'Funky Space Reincarnation' didn't absolutely need to be included) but on the whole, in its deeply personal nature, its unpredictability and its self-determined unwillingness to abide by any preordained structure, Here My Dear as is close to art as R&B is ever going to get.

After leaving The Softies for the first time, the queen of twee Rose Melberg formed Gaze with some like-minded chums. First album Mitsumeru (1998) is another twee-pop gem, scarcely any different to any other (and certainly closer to Melberg's work in Tiger Trap than the Softies). It's got some up songs, it's got some slow songs, but they're all of the artless, clumsy, thoroughly charming librarian pop school that was all the rage for the Olympia kids in the mid to late 1990's. There are songs about jelly beans, songs with names like 'Preppy Villain' and the whole ramshackle pop fun of the exercise is infectiously endearing. As with all of Melberg's work it flirts shamelessly with being annoying but always manages to stay the right side of the line. Melberg did let down Zoe quite badly once by being something of an arse, but that's a different matter, and her records are always speccy charm personified.

Whilst overseeing the endless production line of Giant Sand albums, the ludicrously prolific Howe Gelb also finds the time to make copious albums under variations of his own name, one of which is next on the list. The Listener (2003) is one of Gelb's more accessible excursions into the oblique and focusses more heavily on his instrumental work and occasional Lou Reed impressions than the abstract desert rock and Americana that he tends to centre his records on. There are some surprisingly low-key and graceful piano tracks and piano led songs on The Listener and although it can veer directly into wanting to be Berlin (second track 'Felonious' is a prime example, even stating that it's a Lou steal) it's a delicate Sunday afternoon of an album. There are great jazzy trumpet solos and babbling bass over the indie-blues of the piano work, but this isn't rubbish like Eels bizarrely misconceived notion of how indie bands play the blues, this is the work of someone who has worked hard to really get it, to really understand how different musical forms work and why it's worth using some and discarding others. The Listener is a surprising album for Gelb partly because his work, while always shot through with a mordant sense of humour, can be furious and ragged and instead The Listener is calm, subtle, smart and smarmy, sarky and cool, it's a record that knows it should be playing in the corner of a run-down bar on a hot day, a hyper-ironic take on Ry Cooder's Texico swing.

Pretty brief today but tomorrow is going be one almighty Gabriel fest - it's a whole day of prime Genesis. PROG ON.

Wednesday, 23 January 2013

LaRM day 171 (Gang of Four-Gastr Del Sol)

There are few rock records that have aged as well as Gang of Four's debut, Entertainment! (1979). A punk record that is infinitely more interesting than punk, a dub and funk record with anxious jagged guitars instead of easy rhythm, a rock record entirely at odds with the philosophy of rock, it's an album of astonishing inventiveness, surprising agility and effortless cool. Composed only of those essentials of rock, guitar, bass, drums and vocals, it mines sources entirely without acting subserviently to them and its influence is more all-encompassing now than it was at the time of its release. And to cap it all, it's one of the few genuinely successful records lyrically premised on a truly leftist agenda. Although song lyrics necessarily lead to a kind of simplistic reduction, for a rock record the level of ideological engagement on Entertainment! is astonishingly deep. And besides being dense, thoughtful, smart (and always on the side of the angels), it's got some just great tunes on it. The spiky guitar and fluid bass are what really drive the music and contrast superbly, most notably I suppose on 'Damaged Goods', 'Natural's Not In It', the truly spectacular 'I Found That Essence Rare', but highlighting anything on Entertainment! is fairly pointless, the whole album is one of the truly great records to come out of the punk/post-punk era and its brilliance remains entirely undiminished 34 years later (strange to think that we're further away from the punk era than the punk era was from the Second World War...).

Next is the 'Is It Love?' 7" from 1983. By this point Gang of Four had changed their style fairly dramatically, incoporating elements of white-soul and pop into the sound and although it was an interesting idea at the time, it hasn't aged nearly as well. Indeed the band were in the firing line as sell-outs, charlatans and the album Hard was pretty much panned on its release in any case and its reputation has only grown because it couldn't have got much worse. 'Is It Love?' is a hyper-ironic pop love song but it really isn't a great song and its sound does make you yearn for the spit and fury of their earlier work. B-side, 'A Man with a Good Car' is more of the same.

Finally, the first four album spanning compilation A Brief History of the Twentieth Century, released in 1990 and covering the years 1979-1983, is a fantastic overview, charting their perfect emergence and gradual stylistic smoothing out. The first half is unsurprisingly by far the better, containing glistening, glittering material from Entertainment! and second album Solid Gold ('Cheeseburger' and 'To Hell with Poverty' are just fabulous), and although the later material lacks bite and sounds too audience friendly there are still some amazing songs. Third album, Songs of the Free, had set out a change of style, adding a slicker sheen to the sound and folding in a kind of dance friendly rhythmic style, and it was pretty successful, songs like 'Call Me Up' and 'The History of the World' setting out a blueprint for a moodier kind of pop music that many other bands picked up on. Probably the band's best non-punk song came from this period and 'We Live as We Dream, Alone' is a truly, truly great song. Only the last few songs, from Hard, don't come up to scratch, but it's a little enough failure for a band who had set out new ways of looking at rock music with the simplest of resources.

Unfortunately next we have a few records by the awful Garbage, who for some reason I think I really liked back in the day, starting with their third single, 'Only Happy When It Rains' (1995). Everything about Garbage was like a ready-made parody of themselves and this single proves the point. It's goth-lite, it's silly, it's absurd in its mock-seriousness and it really is mystifying as to what people heard in it. As an absurdist counterpoint to the cheery idiocy of Oasis and the sunny smart-arsery of Blur I suppose it struck a chord but really the bottom line is that it just isn't any good. B-sides 'Girl Don't Come' and 'Sleep' are respectively a terrible dark rock song and a dismal attempt at doing what the Cranes were achieving much more succesfully and the two songs are even less interesting in their attempt to provide a dark pop flipside to the Britpop wave than the A-side.

The self-titled debut album released in 1995 is really still surprisingly bad. It's biggest crime is its total redundancy. There is truly no need for this album ever to have been made and the fact that it was a smash is a damning demonstration of just how polarized the indie scene had become and consequently just how vapid the more commercial side of it had ended up. We can all thank Nevermind for basically breaking fifteen years of astonishing creativity in the indie community, but we'll come on to that later... Anyway, the Garbage album is a lot of hot air blown into a vacuum and it doesn't really warrant any particular attention beyond the fact that something worked for a mass audience. Amazing to think that Curve were much, much better. That's how bad this stuff is. None of the tunes really stick and each one of them may seem to be a powerhouse of production but when it comes down to it this is poorly conceived pop music with uninteresting melodies and a somewhat lacklustre sense of structure and as a result the fact that it's hideously overproduced just leaves it a gluey mass of tiresome noise.

The 'Queer' 7" (1995) A-side is meant to be a creepy, loping gloom-pop song but it's just another tedious dirge masquerading as menace. The B-side is a stereotypical Adrian Sherwood remix which couldn't sound more exactly of its time if it tried (like absolutely everything that Sherwood has ever touched). Likewise with the 'Stupid Girl' 7" (1996). The A-side is at least a half-hearted attempt at a big rock song and the B-side another yawnsome remix of another track from the album, in this case a remix by the band themselves of the bland 'Dog New Tricks'. Similarly we have the 'Milk' 7" (1996) which is not the album version but instead has two boring remixes of the slurringly dull song, this time one by the band and the other by 1996's favourite Bristolian, Tricky.

To be completely honest, the main reason that I bought any of these records was because I got them in their super-limited editions, either entirely encased in plastic, or in cloth covers, or whatever and I thought they'd be worth a ton of money. They never were. Anyway, by the time I had picked up second album, Version 2.0 (1998) I realised that both the band and a rich future were a hopelessly lost cause. Version 2.0 at least has the grace to be unapologetic about its money-grabbing pop ideology and it comes across as more honest (if more essentially unpleasant) as a result. It's a generally easier listen too, although also in fact an even worse record. The pop smarts are more finely tuned and the egregious bludgeoning of the production is more smartly incorporated into the overall structure of the record. The problem is that it's still rubbish. Shirley Manson's gothic self-flagellation is transparently fallacious and the whole thing absolutely reeks of opportunism. And her lyrics, dear lord, are truly appalling. Once again, even the song titles are a parody of themselves: 'I Think I'm Paranoid', 'Medication', 'Wicked Ways', it's all like a joke that wasn't particularly funny to begin with still being told with enthusiasm by a dying comedian. Between Nevermind and The Downward Spiral the truth of "major label indies" was becoming sickeningly clear and although the NME weren't prepared to accept it, Garbage really forced the choice to either give up trying or to dig much, much deeper to find the fertile seeds.

And last for today we have the blessed relief of some challenging avant-composition with Jim O'Rourke and David Grubbs' collaborative Gastr Del Sol and their debut album, The Serpentine Similar (1993). Now this is composition for a modern age, never mind cruddy pop music, if you want to know where should and could be heading, this is the real deal. Difficult, uncomfortable and never prepared to either settle or relax, Gastr Del Sol's sole remit was to experiment, to use every possible resource for manipulation and to create a musical context in which all things are translatable. First tune, the 9-minute piano and vocal workout of 'A Watery Kentucky' shows off O'Rourke and Grubbs' avant tricks pretty adeptly, snakily winding it's way around a central motif which changes only subtly but transforms completely as a result. Essentially that's the trick for all these pieces, from the superb juddering guitar thud of 'Ursus Arctos Wonderfilis' to the staggering piano on 'Eye Street', a central core around which themes wind and unwind with the occasional vocal embellishment (which basically tends to constitute of O'Rourke mumbling about something or other). 'For Soren Mueller' is similar in some ways to the work of June of '44, with rattling drums and jittery, spindly guitar lines which suddenly and unpredictably briefly break out into frenzied spattering rhythm and noise. It's all closest in spirit to post-rock, if you want to classify it, but it really most appropriately sits in a modern classical composition framework than a rock one and it sets out a wealth of possibilities for exploration and innovation while being quite comfortable to exist in its own isolated context.

Next is the 'Is It Love?' 7" from 1983. By this point Gang of Four had changed their style fairly dramatically, incoporating elements of white-soul and pop into the sound and although it was an interesting idea at the time, it hasn't aged nearly as well. Indeed the band were in the firing line as sell-outs, charlatans and the album Hard was pretty much panned on its release in any case and its reputation has only grown because it couldn't have got much worse. 'Is It Love?' is a hyper-ironic pop love song but it really isn't a great song and its sound does make you yearn for the spit and fury of their earlier work. B-side, 'A Man with a Good Car' is more of the same.

Finally, the first four album spanning compilation A Brief History of the Twentieth Century, released in 1990 and covering the years 1979-1983, is a fantastic overview, charting their perfect emergence and gradual stylistic smoothing out. The first half is unsurprisingly by far the better, containing glistening, glittering material from Entertainment! and second album Solid Gold ('Cheeseburger' and 'To Hell with Poverty' are just fabulous), and although the later material lacks bite and sounds too audience friendly there are still some amazing songs. Third album, Songs of the Free, had set out a change of style, adding a slicker sheen to the sound and folding in a kind of dance friendly rhythmic style, and it was pretty successful, songs like 'Call Me Up' and 'The History of the World' setting out a blueprint for a moodier kind of pop music that many other bands picked up on. Probably the band's best non-punk song came from this period and 'We Live as We Dream, Alone' is a truly, truly great song. Only the last few songs, from Hard, don't come up to scratch, but it's a little enough failure for a band who had set out new ways of looking at rock music with the simplest of resources.

Unfortunately next we have a few records by the awful Garbage, who for some reason I think I really liked back in the day, starting with their third single, 'Only Happy When It Rains' (1995). Everything about Garbage was like a ready-made parody of themselves and this single proves the point. It's goth-lite, it's silly, it's absurd in its mock-seriousness and it really is mystifying as to what people heard in it. As an absurdist counterpoint to the cheery idiocy of Oasis and the sunny smart-arsery of Blur I suppose it struck a chord but really the bottom line is that it just isn't any good. B-sides 'Girl Don't Come' and 'Sleep' are respectively a terrible dark rock song and a dismal attempt at doing what the Cranes were achieving much more succesfully and the two songs are even less interesting in their attempt to provide a dark pop flipside to the Britpop wave than the A-side.

The self-titled debut album released in 1995 is really still surprisingly bad. It's biggest crime is its total redundancy. There is truly no need for this album ever to have been made and the fact that it was a smash is a damning demonstration of just how polarized the indie scene had become and consequently just how vapid the more commercial side of it had ended up. We can all thank Nevermind for basically breaking fifteen years of astonishing creativity in the indie community, but we'll come on to that later... Anyway, the Garbage album is a lot of hot air blown into a vacuum and it doesn't really warrant any particular attention beyond the fact that something worked for a mass audience. Amazing to think that Curve were much, much better. That's how bad this stuff is. None of the tunes really stick and each one of them may seem to be a powerhouse of production but when it comes down to it this is poorly conceived pop music with uninteresting melodies and a somewhat lacklustre sense of structure and as a result the fact that it's hideously overproduced just leaves it a gluey mass of tiresome noise.

The 'Queer' 7" (1995) A-side is meant to be a creepy, loping gloom-pop song but it's just another tedious dirge masquerading as menace. The B-side is a stereotypical Adrian Sherwood remix which couldn't sound more exactly of its time if it tried (like absolutely everything that Sherwood has ever touched). Likewise with the 'Stupid Girl' 7" (1996). The A-side is at least a half-hearted attempt at a big rock song and the B-side another yawnsome remix of another track from the album, in this case a remix by the band themselves of the bland 'Dog New Tricks'. Similarly we have the 'Milk' 7" (1996) which is not the album version but instead has two boring remixes of the slurringly dull song, this time one by the band and the other by 1996's favourite Bristolian, Tricky.

To be completely honest, the main reason that I bought any of these records was because I got them in their super-limited editions, either entirely encased in plastic, or in cloth covers, or whatever and I thought they'd be worth a ton of money. They never were. Anyway, by the time I had picked up second album, Version 2.0 (1998) I realised that both the band and a rich future were a hopelessly lost cause. Version 2.0 at least has the grace to be unapologetic about its money-grabbing pop ideology and it comes across as more honest (if more essentially unpleasant) as a result. It's a generally easier listen too, although also in fact an even worse record. The pop smarts are more finely tuned and the egregious bludgeoning of the production is more smartly incorporated into the overall structure of the record. The problem is that it's still rubbish. Shirley Manson's gothic self-flagellation is transparently fallacious and the whole thing absolutely reeks of opportunism. And her lyrics, dear lord, are truly appalling. Once again, even the song titles are a parody of themselves: 'I Think I'm Paranoid', 'Medication', 'Wicked Ways', it's all like a joke that wasn't particularly funny to begin with still being told with enthusiasm by a dying comedian. Between Nevermind and The Downward Spiral the truth of "major label indies" was becoming sickeningly clear and although the NME weren't prepared to accept it, Garbage really forced the choice to either give up trying or to dig much, much deeper to find the fertile seeds.

And last for today we have the blessed relief of some challenging avant-composition with Jim O'Rourke and David Grubbs' collaborative Gastr Del Sol and their debut album, The Serpentine Similar (1993). Now this is composition for a modern age, never mind cruddy pop music, if you want to know where should and could be heading, this is the real deal. Difficult, uncomfortable and never prepared to either settle or relax, Gastr Del Sol's sole remit was to experiment, to use every possible resource for manipulation and to create a musical context in which all things are translatable. First tune, the 9-minute piano and vocal workout of 'A Watery Kentucky' shows off O'Rourke and Grubbs' avant tricks pretty adeptly, snakily winding it's way around a central motif which changes only subtly but transforms completely as a result. Essentially that's the trick for all these pieces, from the superb juddering guitar thud of 'Ursus Arctos Wonderfilis' to the staggering piano on 'Eye Street', a central core around which themes wind and unwind with the occasional vocal embellishment (which basically tends to constitute of O'Rourke mumbling about something or other). 'For Soren Mueller' is similar in some ways to the work of June of '44, with rattling drums and jittery, spindly guitar lines which suddenly and unpredictably briefly break out into frenzied spattering rhythm and noise. It's all closest in spirit to post-rock, if you want to classify it, but it really most appropriately sits in a modern classical composition framework than a rock one and it sets out a wealth of possibilities for exploration and innovation while being quite comfortable to exist in its own isolated context.

Tuesday, 22 January 2013

LaRM day 170 (France Gall)

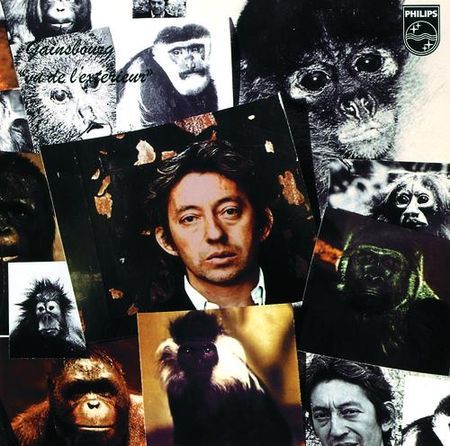

And so we come to the greatest pop singer of all time (although I'm referring here to only five years of her lengthy career). OF ALL TIME. It's the immortal and untouchable France Gall. Being untouchable is, I suppose, an ironic comment in light of the fact that, unbeknowst to her, one of her biggest hits was about fellatio. And so we return, as all roads seem to, to Serge Gainsbourg, who wrote a handful of songs for Gall, including the aformentioned 'Les Sucettes'. There's some amazing footage of Gall and Gainsbourg discussing 'Les Sucettes'. The 18 year old Gall is asked what she thinks the song is about and replies that it's clearly about a girl who enjoys lollipops. Her face when Gainsbourg enlightens her is a picture of mortification and Gall notoriously barracked herself in her flat for some weeks afterwards. In many ways it's a real shame either that Gall didn't know what was going on or that it happened at all because the 'Les Sucettes' affair was the end of the songwriting partnership between the pair, which had by that time produced some of the finest pop music ever comitted to vinyl. The debut album, named Les Sucettes also after the success of the single, and released in 1965, is a superb demonstration of the art of throwaway pop, containing twelve of the purest examples of the form. Gall's high, uncertain, girlish voice is the perfect vehicle for this stuff and absolutely makes it come alive. It's also all unmistakeably French, with a dedication to an uneasy balance between the childish and the mature (at the risk of soundy a bit creepy, the cultural as well as musical precedents for rubbish like Joe le Taxi are all in Gall's work, if you follow my meaning) and Gall's personality is demonstrative of that uncomfortable imperative, which works so perfectly for pop music. The songs on Les Sucettes are all fairly straightforward pop with no unnecessary frills, no experimentalism, no messing about. We have pop-ballads ('Il Neige', the yearning 'Bonsoir John-John'), thudding dansefloor pop ('Tu n'as pas le Droit') silly, childish singalongs ('Oh! Quelle Famille', 'J'ai Retrouve Mon Chien') and more controlled contemporary pop (the brilliant and jazzy 'L'Echo', the superbly structured 'La Rose des Vents', 'Quand on est Ensemble'). It's all absolute gold, with not a wasted note, not a wasted moment, and it's an object lesson in why the French were the true masters of this stuff in the 1960's.

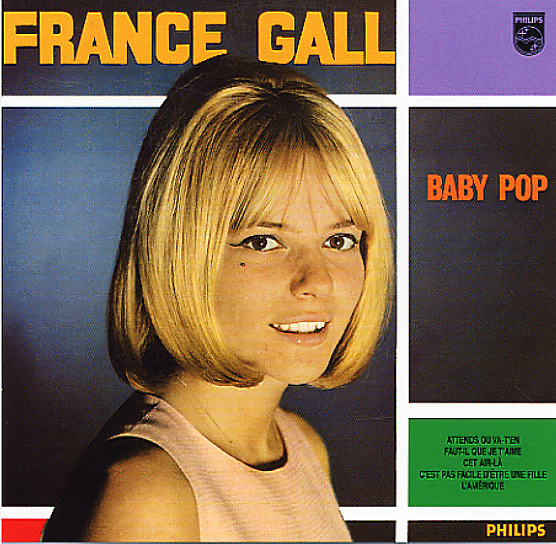

The hyper-pop side of Gall was played up on 1966's Baby Pop LP (as expressive an album title as you can get I guess). It's super-jaunty, lively, bop-about stuff, but with a distinctly nasty undercurrent running through it (courtesy of Gainsbourg's typically vicious approach to songwriting - most of the songs on Baby Pop were recorded at the same time as those on Les Sucettes) subtly railing against French sentimentality, American imperialism and all kinds of other stuff which apparently Gall didn't understand at all. It's easy to just enjoy the pop though, and it really is pop to the max on Baby Pop. 'L'Amerique' is a fantastically daft yahoo of a song, the title track is a pounding slab of aggro-pop and almost certainly the finest song of Gall's career, the pristinely melodic organ swirl of 'Cet Air La', is on the album, making it worth the price of admission alone. There are moments of respite from the pop onslaught, the gently insistent 'C'est Pas Facile d'etre une Fille' and the shuffling ramble of 'On se Ressemble Toi et Moi' for instance, but for the most part this is blisteringly propulsive pop music of the absolutely highest order.

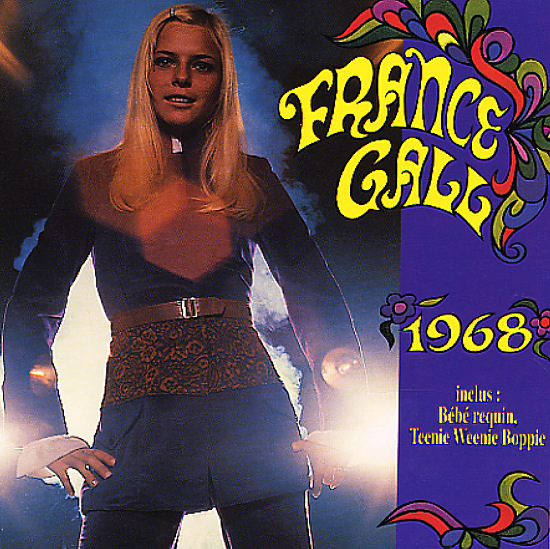

In 1967 Gall stepped boldly into the psychedelic era by making the 1968 album. As freak-out albums go it's pretty straight, but as pop records go it's a bold attempt at being "out there" with some groovy ragga rhythms ('Avant la Bagarre'), a woozy sitar weird-out ('Chanson Indienne') and an album sleeve to absolutely die for. It's got a couple of dud tunes on it ('Chanson Pour Que Tu M'aimes un Peu' is a bit of a bore), but when it's good, my word it's good. In some ways the best pop songs on 1968 are the best pop songs she ever made. Opener 'Toi Que Je Veux' is a charming bit of fluttering balladry, Gainsbourg's only reclaimed song on the album, 'Nefertiti', is a priceless exercise in Asiatic poor taste made glorious by Gall's brilliantly cheerful interpretation, and album closer 'Made in France' is a barnstorming bit of culturally aggressive super-pop. It's a fantastic (in all senses) album and although it really marked the end of Gall's most glorious period, it really is a remarkably fine piece of Gallic pop-art.

Next up we're shifting chronology a bit by doing the compilation Poupee de Cire, Poupee de Son (2001) which covers Gall's career from 1963-1968 only. Most of the songs on here that aren't on the three albums above are absolutely superb, especially the earliest stuff, most of which was Gainsbourg's work. There's the Eurovision entry (the title song) which is a mind-blowing piece of pop music, the truly astonishing 'Laisser Tomber les Filles' and 'N'ecoute pas les Idoles', both of which show off Gainsbourg's gift for effortlessly combining pop musicality with aggressively snide lyrical themes. There are some trying moments (the self-explanatory 'Jazz-a-Go-Go' and similar 'Pense a Moi' are a bit much and 'Dis a ton Capitaine' is a little annoying) but any failures are dramatically outweighed by brilliance. The indescribably charming 'Christiansen' is just lovely, as is 'Ne dis pas aux Copains', and there's cherry pop in 'Polichinelle' and the children's tune 'Sacre Charlemagne'. In truth even when the tunes aren't utterly brilliant, Gall's wonderfully artless delivery and wide-eyed personality always are.

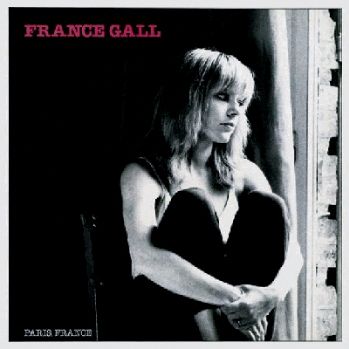

One of the ultimate proofs of just how pristine this pop is, is the fact that of the 50 songs we've just worked through only one breaks the 3 minute mark. Although she kept releasing singles throughout the 1970's, her career had foundered and label and management changes didn't help. She didn't release any albums between 1967 and 1976 when she put out a weak self-titled album, followed the next year by the disastrous Dancing Disco LP. In 1980 she had a sudden and unexpected rennaissance when she released the album Paris, France, which is the next one on our list. It's unsurprisingly a very different kind of record to those she was releasing in the 60's. This is smooth, adult-pop with fretless bass, heavy synths and a somewhat overwrought production. The single 'Il Jouait du Piano Debout' (the 7" of which would have been next, but the B-side is also on the album so we'll skip it) was a smash hit in France and effectively allowed Gall to remain in the business to this day. It's an inoffensive bit of jazzy sophisti-pop in a very 80's French style (ie, corny even by general 80's pop standards - what happened to French pop? It was the best in the world and became pretty much the worst by the late 70's) and there were worse records released pretty much everywhere that year, but you can't help but think back to the glory years. Anyway, the album as a whole is an overblown affair with Gall's thin voice now simply thin rather than charming (mainly because she's actually trying to sing properly) and it's all fairly bland, with the occasional light spot ('Plus Haut' is quite nice, but it's helped by the fact that it comes after the abysmal 'Parler Parler'). It's not a disaster by any stretch and showed that Dancing Disco was an uncomfortable aberration, and bearing in mind Gall was no longer the teen-pop sensation it's not an inappropriate development, it just isn't a particularly good one.

It's more of the same for 1981's Tout Pour la Musique which continues this theme of the mature songwriting, and to be honest it's overall a better album with stronger songs ('Diego Libre dans sa Tete' is pretty decent) and the whole thing has a peculiar air of being a French straight version of early Kate Bush. Gall's voice is tretched to its limited utmost and she trills and quivers in a peculiar but fairly interesting way and there are choppy workouts (closer 'Ceux Qui Aiment') but it's still all just too Europop to be taken really seriously. It's a shame because you can hear some genuinely decent stuff in here but it's just presented as too corny a package to really be enjoyable. There is, unsurprisingly, some truly terrible stuff here too but taken in the context of its time and its history it could be much worse.

Worse is presented right now, with 1984's dismal Debranche. The awful, desperate cover tells the story really. This is glossy, shiny, cruddy Francopop at its most anodyne. The synths are just terrible, the production has mullet-headed engineers all over it and the tunes aren't throwaway in a fun sense they just should have been thrown away. Again though, there's some undeniable structure in some of this stuff and the odd fun key change makes a big difference. But Gall's voice is so nondescript as to be scarcely noticeable and the whole exercise sounds like something that would have been rejected from the Who's That Girl soundtrack.

More of the same disappointing sludge composes most of 1987's Babacar, but at least this time around the cover doesn't look like a Club 18-30 promo poster. There's nothing much to really say about Babacar that I haven't covered in the previous two albums, other than that it's a little bit worse again.

And so we leave France Gall with the dismal 1996 album, France, which is some new material and re-recordings of some songs from the grim second half of her career. It's such a shame that we've had to devote as much time to the shoddy second half of her career as to the glorious, golden, glittering first half. But there we are, that's the thing about being a survivor in the music world, it's rare indeed that you're ever going to be able to make decent records later in your career. I'm not going to say much about the smooth soul grooves of France, except that you can hear so clearly what was intended and maybe, just maybe, there was a Sade album in here (although personally I would consider that little enough), but it's been so obscured by clumsy production and half-hearted performances that all we're left with is a flimsy bit of cod-soul, cheesy rare groove and pop music with two left feet. To my mind though it really doesn't matter what France Gall did after 1968, nor what she may do in the future, all is both forgiven and forgiveable because of 5 years of the greatest chart pop ever produced.

The hyper-pop side of Gall was played up on 1966's Baby Pop LP (as expressive an album title as you can get I guess). It's super-jaunty, lively, bop-about stuff, but with a distinctly nasty undercurrent running through it (courtesy of Gainsbourg's typically vicious approach to songwriting - most of the songs on Baby Pop were recorded at the same time as those on Les Sucettes) subtly railing against French sentimentality, American imperialism and all kinds of other stuff which apparently Gall didn't understand at all. It's easy to just enjoy the pop though, and it really is pop to the max on Baby Pop. 'L'Amerique' is a fantastically daft yahoo of a song, the title track is a pounding slab of aggro-pop and almost certainly the finest song of Gall's career, the pristinely melodic organ swirl of 'Cet Air La', is on the album, making it worth the price of admission alone. There are moments of respite from the pop onslaught, the gently insistent 'C'est Pas Facile d'etre une Fille' and the shuffling ramble of 'On se Ressemble Toi et Moi' for instance, but for the most part this is blisteringly propulsive pop music of the absolutely highest order.

In 1967 Gall stepped boldly into the psychedelic era by making the 1968 album. As freak-out albums go it's pretty straight, but as pop records go it's a bold attempt at being "out there" with some groovy ragga rhythms ('Avant la Bagarre'), a woozy sitar weird-out ('Chanson Indienne') and an album sleeve to absolutely die for. It's got a couple of dud tunes on it ('Chanson Pour Que Tu M'aimes un Peu' is a bit of a bore), but when it's good, my word it's good. In some ways the best pop songs on 1968 are the best pop songs she ever made. Opener 'Toi Que Je Veux' is a charming bit of fluttering balladry, Gainsbourg's only reclaimed song on the album, 'Nefertiti', is a priceless exercise in Asiatic poor taste made glorious by Gall's brilliantly cheerful interpretation, and album closer 'Made in France' is a barnstorming bit of culturally aggressive super-pop. It's a fantastic (in all senses) album and although it really marked the end of Gall's most glorious period, it really is a remarkably fine piece of Gallic pop-art.

Next up we're shifting chronology a bit by doing the compilation Poupee de Cire, Poupee de Son (2001) which covers Gall's career from 1963-1968 only. Most of the songs on here that aren't on the three albums above are absolutely superb, especially the earliest stuff, most of which was Gainsbourg's work. There's the Eurovision entry (the title song) which is a mind-blowing piece of pop music, the truly astonishing 'Laisser Tomber les Filles' and 'N'ecoute pas les Idoles', both of which show off Gainsbourg's gift for effortlessly combining pop musicality with aggressively snide lyrical themes. There are some trying moments (the self-explanatory 'Jazz-a-Go-Go' and similar 'Pense a Moi' are a bit much and 'Dis a ton Capitaine' is a little annoying) but any failures are dramatically outweighed by brilliance. The indescribably charming 'Christiansen' is just lovely, as is 'Ne dis pas aux Copains', and there's cherry pop in 'Polichinelle' and the children's tune 'Sacre Charlemagne'. In truth even when the tunes aren't utterly brilliant, Gall's wonderfully artless delivery and wide-eyed personality always are.