After Seefeel split up Mark Clifford released a couple of EPs and an album under the name Disjecta (not to sound like a sort of grime artist, but after a Samuel Beckett essay). It's similar to Seefeel's post-ambient electronica, but even more clinical. The album, Clean Pit and Lid (1996) is slick and slippery and it uses its status as a Warp release to show off just how much the Aphex Twin wasn't the only person capable of redefining the electronica genre, from keyboard noodling into a sort of post-Autechre mathematical project. It's determined and spacious, and it has a habit of breaking down into headache inducing, tinny repetitions. It's certainly clever and it's certainly compelling, but it's all head and no heart and the electronica by way of shoegaze that he made in Seefeel I think was much more engaging than the Disjecta work.

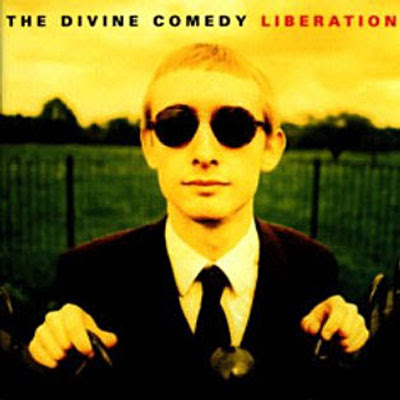

To kick off a Divine Comedy marathon should have been the 'Europop' single from 1992 but none of the three extra songs on it are anywhere to be found on the legitimate internet, so we have to start instead with the second album (and first widely available), Liberation (1993). As an album Liberation is something of a mess, but as a statement of intent it couldn't possibly be clearer. Neil Hannon's ambition to be simultaneously F Scott Fitzgerald, Anthony Trollope, Collette, Cole Porter, George & Ira Gershwin, Ray Davies and Oscar Wilde is remarkably well established by the personality he adopts and portrays on Liberation. The themes, the preoccupations, the effete Englishness by way of Ireland are all clearly set out and in many ways, although the album can be an irritation, you have to marvel at the completeness of Hannon's vision at such an early stage. Musically there's all sorts going on in the chamber pop framework of Liberation from stupid and annoying out and out pop song ('Europop', 'The Pop Singer's Fear of the Pollen Count' - always ironic though) to superb Brackhage style sound experiments ('Europe By Train'). There's Evelyn Waugh style throwback irony ('Your Daddy's Car'), to renderings of Fitzgerald in pop song ('Bernice Bobs Her Hair') by way of tributes to Mr Benn ('Festive Road'). There are a few pointers to the great records Hannon would make, and there's a truly beautiful piece in album closer 'Lucy', one of Wordsworth's most affecting poems turned respectfully into a delicate pop song, but the album is too sprawling, lacking in focus and sounds too much like a collection of disperate ideas rather than a coherent album.

That album was follow-up, Promenade (1994) an arch, ornate record of remarkable sophistication, both musically and conceptually. Many people find the Charles Ryderish nature of Hannon's character, which is at its apex on Promenade, too much to take but personally I feel a great affinity for it. The entirely fictitious universe of rolling lawns, country houses and ballrooms that he creates is similar to that intellectual upper classism that Stephen Poliakoff finds so attractive, and so do I. The conceipt is one thing, the execution of it is another, and Hannon's masterstroke with Promenade is to populate it with beautiful, stately pop songs, performed with no pop instruments at all. The only concession is the drum kit, the rest is piano, woodwinds and strings and the result is a record that seems on the surface a fairly straight, if arch, pop album but that is in fact an acutely anti-pop/rock one. It makes no active concessions at all when you listen to it closely and this fits absolutely with the broader false-nostalgia theme of the album. It's really quite something. There are a couple of missteps with the rollicking 'A Drinking Song' and 'A Seafood Song' but that's only because they muddy the waters of melancholic, bucolic nostalgia that the rest of the album conjures. 'The Summerhouse' is the archetype of Hannon's approach at this time, graceful, and delicately paced, with cor anglais marking out the melody while he delivers a grandstanding vocal outlining what can only be a pretence of the romance of an upper-class childhood. It's lovely stuff. Really Promenade is romantic throughout with its tales of country house balconies, lovers running through the rain and freewheeling bicycle rides. It also ends with what I think is one of Hannon's most directly moving songs, 'Tonight We Fly'.

The next step was the one that finally divided critics once and for all. Casanova (1996) found Hannon turning his foppish, intellectual alter ego and making him a lascivious, leering creature, prowling Europe in search of prey. The songs are even more over the top and preposterously ambitious than ever and although there are some straight ahead pop songs, everything involves such ornate orchestration that it seems like a towering piece of showing off. It's a big, bold record and one that seems unprepared to make any concessions to accusations of vainglory. That's what hacked many people off and it's what I love about Casanova. I don't think Hannon has every knowing courted popularity in a mainstream sense and even though he has bemoaned a lack of financial reward in the past, I can't help but think that he knows as well as anyone that his career has been all about rowing against the tide. It's a band effort this time around and the music, although heavy with string arrangements, is for the most part principally based around the standard guitar, bass, drums set-up. There are very clear references to Scott Walker's records as well as to pop cultural ephemera and the orchestration is courtesy of Joby Talbot who plays an increasingly prominent role in the Divine Comedy records from this point. In fact it's Talbot's contributions that really make Casanova fly. The best songs are the ones in which Hannon reverts to the more pseudo-romantic mode and critical modes ('A Woman of the World' and especially closer 'The Dogs and the Horses' are fabulous, and 'Middle-Class Heroes' throws some successful cheap shots). It's an easy album to hate, I can understand that, but I think it's an easy album to love too.

I think Hannon sensed that it might be possible to take a similar approach to that of Casanova and up the ante in terms of the dramatic arrangements, but tone down the arch attitude and A Short Album About Love (1997) does just that. With its 30-piece orchestra foundations, it's an album of truly vaulting ambition and Hannon's deep croon is forced to reach new levels of control to maintain dominance over the music. The songs are great, indulging the Scott Walker fixation to the absolute limit, with lush, romantic leanings predominating throughout. 'Everybody Knows (Except You)' is lovely, 'The Pursuit of Happiness' charmingly snide, 'I'm All You Need' grand without being grandiose.

1998's Fin de Siecle assimilates all of the various approaches of the Divine Comedy's previous records and creates a monolithic piece of grandstanding pop, with a bitingly gloomy edge. There are massive pieces of orchestration from Talbot which drive along songs which in some cases might not otherwise stand up. It does also have the bitingly nasty, but sadly utterly irritating 'National Express', but in some ways that song is representative of an element of the album as a whole. There's something very dark and basically misanthropic about Fin de Siecle - elements which have never been much on show previously. Any romantic sense is completely taken apart by context. If 'Commuter Love' weren't so drily sarcastic it would be romantic and that's true of a lot of the album. It's as if Hannon is saying that if we didn't get that he was just being horrible before, he'd better make it crystal clear this time around. It's a shame because I think it's a fantastically well constructed record with some gloomily brilliant songs. There's silliness (the Kurt Weillisms of 'Sweden' for instance) and some tricksy but cheap social wordplay ('Generation Sex' is righteous but perhaps too easily curmudgeonly) - there always is with Divine Comedy records, but there's also some wonderful stuff ('The Certainty of Chance', 'Sunrise' which is a lovely finish).

No comments:

Post a Comment