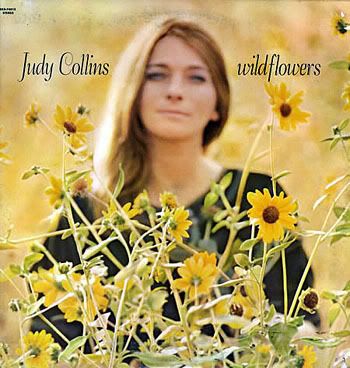

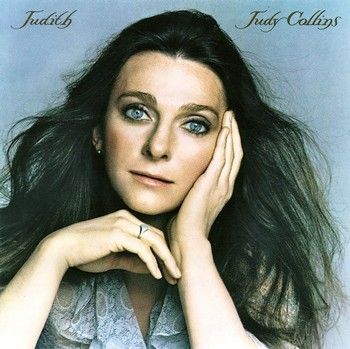

If there were any doubts about Collins' purist folk approach they were confirmed once and for all by the release of Who Knows Where the Time Goes (1968), the general style of which is much closer to country than to folk, and features a host of guest musicians, most of whom played country as standard. It also heralded the return of the more strident, harsher end of Collins' range which is a shame, not least because this is where her voice sounded corniest. However, as ever, she is an adept interpreter of other people's songs and her Cohen songs this time out are as bold and impressive as ever. Nobody, but nobody, should ever cover Sandy Denny's songs because nobody, but nobody, can sing like she could, but people insist on doing it and failing, and Collins is no exception. The two things that can be said in favour of Collins' cover of 'Who Knows Where the Time Goes' are that (i) Collins was so in tune with the time, and had such impeccable taste that she had heard Sandy's demo and recorded the song before even Denny herself had recorded it properly, and (ii) it's a much better and truer version than most people have managed. Finally we skip over a few years and a few albums to 1975's Judith. By this point Collins' work had pretty much been reduced to a mushy kind of Julie Covington-y mawkish schmaltz, but even then there are flashes of something truer and clearer. The real problem is the overly dense orchestration and weepy arrangements. The same kind of stylistic turn had been taken by many of her contemporaries so it's hard to blame her really, and people had done a lot worse, but with its MOR arrangements and rather lackadaisical performance Judith isn't much to shout about.

Colourbox were something of an anomoly in terms of the 4AD roster, as they constructed their songs as much out of samples as live instrumentation and as such they were a fairly pioneering act. Their records are abstract synthesised pop songs composed of a dense mass of not only musical samples but occasionally also snippets from adverts and TV shows, and although it sounds faintly quaint now, it was pretty groundbreaking stuff at the time. Underpinning the samples (rather than the other way around) are the guitars and bass which create the essential musical framework, over which the samples are layered. What's remarkable is that rather than just being a mess, the songs on Colourbox (1985) are very distinctly R&B, white soul and dub pieces (Lorita Grahame's vocals are brilliantly aggressively soulful), whole songs which work absolutely in their own right, quite apart from the technological poking around going on. There is still an inexplicable dark, slightly gloomy, edge about the album, which I suppose came from simply being part of the 4AD stable. Nonetheless, you can easily hear how 'Pump Up the Volume' (which Colourbox made under the M/A/R/R/S name) is related to this stuff.

As an easy listen Alice Coltrane's Universal Consciousness (1971) doesn't even register, but as an astonishingly pioneering work of psychedelic free jazz it's peerless. The influence of this album is felt throughout the experimental, and particularly electronic, musical worlds. It is a totally free-ranging and unrestrained exercise in musical self-indulgence but it is also a remarkably self-assured piece of abstract jazz which leaves no room for doubt about the clarity of Coltrane's vision. From low-level drones, to free-form freakouts on ethnic pipes and strings it's all amazing stuff and while it may fall short of its intention of saying something truly universal, it does manage to create an atmosphere of total inclusiveness. It's certainly a challenging work in some ways, but its essence is throughly admirable.

And last up for today it's two of John Coltrane's greatest and most well regarded albums, starting with his only Blue Note lead album Blue Train (1957). Coltrane was erudite and intellectually engaged both as a person and as a performer and one can only wonder what he might have been achieving following Blue Train if he hadn't had such a penchant (like everyone around him) for heroin. Blue Train was conceived and composed specifically for the Blue Note recording session, and with the exception of a lovingly rendered 'I'm Old Fashioned', it's all Coltrane's specific take on the hard bop style. It's fantastically played and beautifully structured with Coltrane's sax sounding both energised and comfortable, there's no shrill parping to be heard on Blue Train, it's all fantastically considered and subtle. Lee Morgan gives some prime backing on trumpet and the rhythm section are singularly respectful. It's all really wonderful stuff and no surprise that it's such an iconic piece of work. Likewise 1965's A Love Supreme. The two records could hardly be more different but they are each towering moments both in Coltrane's career and in jazz history. A Love Supreme is effectively a single four-section piece, a hymn to God (thanking him for helping Coltrane get off the drugs and the booze apart from anything else), the hard bop giving way to the free jazz style that would become more prevalent. There's a seriously experimental edge to A Love Supreme that jars slightly against the more post-trad hard bop style, but it's a fascinating insight into how the one morphed into the other, and the process is encapsulated almost entirely on A Love Supreme. It's a more aggressively challenging listen than Blue Train is, no question, but it pointed out the road ahead for jazz in a way that nobody else had seen quite so clearly, and it's a truly extraordinary piece of work.

No comments:

Post a Comment