OK so here we go on a 16 album Brian Eno odyssey. For the sake of getting everything in, I'm including all Eno's collaborations with other individual composers under his name, even if he's credited second, so that means that we start with 1973's collaboration with Robert Fripp, No Pussyfooting. Not the easiest start to our Eno session, No Pussyfooting is experimental composition without compromise and although it does set out Eno's nascent ambient structures it also has a heavy dose of Fripp's absurdly overcomplicated treated guitar work. The first of the two pieces, 'The Heavenly Music Corporation' is pretty lovely though, with Fripp's guitar being treated in such a way as to create some really lovely surging and subsiding drone waves against which he then sets an unusually understated display of his "Frippertronic" reverb drenched, high end soloing. The whole album was recorded using ever developing tape loops and building up sounds on the loop as it came round the tape heads, and it's a clever early demonstration of the potential of such a recording process. The second piece, 'Swastika Girls' though is a little less successful, partly because it is busier and doesn't allow the space for the listener to disappear into that the first piece grants. Nonetheless it's still a fantastically innovative piece of work, indebted far more to avant classical composition then rock music, and besides being perhaps the earliest ambient record as we think of it now it also marked Eno out particularly as a truly creative thinker in a cultural sphere usually unforgiving of real innovation. Also, can anybody explain the cover to me? I get the room of mirrors being symbolic of the tape loop recording system, but why are they playing cards with a deck of nudie cards?? The reissue that I have also includes the whole album played backwards, which interestingly sounds like a different take on the same process, and also 'The Heavenly Music Corporation' played at half-speed which sounds like the ultimate drone experiment and puts most ambient music made since the late 1980's to shame.

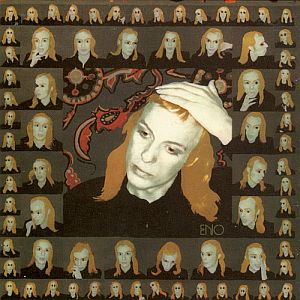

And so on to Eno's debut solo proper, Here Come the Warm Jets (1973). This is glam rock as performed by an art-rock cabaret, a superbly uncompromising demonstration that whatever people thought pop music was in 1973, it could be something very different. With a handful of exceptions the songs on Here Come the Warm Jets are relatively straightforward, but musically Eno creates a dense and entirely idiosyncratic set of arrangements in which all instrumentation is manipulated in one way or another to make it sound either other-worldly or else nothing like it originally sounded and as a result the album is a totally free and whimsical approach to pop music unlike any other at the time. The influence of the record has been immense (every element of 'Blank Frank' has been stripped and ripped off a million and one times for instance) and to listen to it now, it still sounds like a leap forward both in terms of how to treat pop songs and how to write and record them. Eno's other relatively clean "pop" album, 1974's Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy) is very slightly less well-regarded but personally I actually prefer it. There are more specific and deliberate quirks on Tiger Mountain which I find more exciting than the more broad-brush show-off pop experimentalism of Warm Jets. It's also less joyfully uninhibited, there's a denser, darker mood to Tiger Mountain, and there's also a feeling that the songs were much more closely scrutinised as they were written and recorded. The idea that challenging art-rock could be this accessible and this straightforwardly enjoyable is remarkable in itself, but the fact that unlike a lot of art-rock this is genuinely incredibly clever stuff just makes the whole enterprise even more extraordinary.

Finally today is one of the greatest albums of the 1970's and one of the most important in terms of the vastness of its influence. Another Green World (1975) was the point at which Eno stripped down the melodicism of his pop music and built up in its place the ambient atmospherics that he would go on to explore in greater detail. What's remarkable about Another Green World is the way in which Eno constructs the whole album with such concision and such precise attention to detail, never allowing a tune or song to over-reach or outlive its interest, and so these pieces are brief, there's no ambient noodling here at all, and all highly evocative. There are dark edges to some of these tunes and some are lighter than air, and despite the fact that the sound and tone of each piece is markedly different from the rest, each plays a vital part in the whole. As far as ambient music goes there's too much life, too much melody and too many songs (there are a handful of lovely skewed melodic songs amongst the instrumental pieces on Another Green World) for it to ever be classified as an ambient album and there are too many spectral and atospheric pieces for it to ever be called a rock or pop album. It's a pivotal record which has gone on to underpin whole swathes of musical development and while that's fairly remarkable in itself, Another Green World's greatest achievement is that it has scarcely dated and still sounds fantastic today.

No comments:

Post a Comment